Private sector offers temptation after NIMASA, but I’m cut out to serve

Pay attention to operating environment; infrastructure; security; funding; education

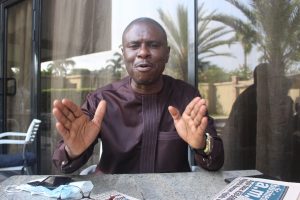

Often described as a transformational leader; a turnaround management expert, or an organizational renewal expert, Dakuku Peterside, PhD, sees himself as a team player who can deliver unusual results working with others. The Rivers State-born politician and a former commissioner of works in Rivers State, has exercised his wealth of experience as a radical reformer at the helm of a national public institution, which says a lot about the quality of his mind; especially going a step further to put down this practical knowledge in a forthcoming book, ‘Strategic Turnaround: Story of a Government Agency’.

Business A.M.’s team of PHILLIP ISAKPA and CHARLES ABUEDE sat down with DAKUKU ADOL PETERSIDE, former Director-General and Chief Executive Officer of Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA), to look at the nexus between his expressed thoughts, contained in his forthcoming book, and his management thinking as applied in his four years stint at the helm of NIMASA. You will find him very forthcoming and effusive in his response to questions. Enjoy reading the EXCERPTS: Photo Credit: JAIYEOLA ISAAC

Let us start with what the top British Professor Emeritus, Chris Bellamy, said about your forthcoming book, Strategic Turnaround. He said it was a radical turnaround, your approach to leading NIMASA. What did you meet at NIMASA and why do you think Professor Bellamy considered what you did radical in a government agency like NIMASA?

When we were appointed at NIMASA, we were given one charge – “Go and reposition the agency”. At the time, we did not know the depth of the challenge. But when we got there, we discovered that there was a reputation challenge and that the human beings who were running the system were demotivated. There was a challenge with culture and with the systems in place. And the agency had lost the trust of those she was regulating. In summary, that was the kind of challenge we met on ground. In essence, the whole of the organisation was challenged. Perhaps Professor Bellamy referred to it as radical, because what we did was technically speaking, a 180 degrees turnaround in performance output. The moment we settled down, we commenced with the diagnosis of what the problem was. And we didn’t just do it by bringing consultants, we sat with the people in the agency, listened to them, heard their ideas and challenges. And when they proposed their solutions, we also got in other stakeholders to cross fertilize ideas.

At the end of the day, we all had a common understanding of what the challenges were; we all worked together to find solutions to the challenges we identified; and at the end of the day, it was crystal clear, where the problem was. We designed solutions around a number of key initiatives. We began the implementation; but we realized that you cannot ask people to go in a new direction if they are demotivated or if trust has been broken. One of the things we needed to do was to reset our human capacity, ensure that the organization is going to give priority attention to their pain points, welfare, and their challenges. We needed to also build their knowledge capacity and give them new energy. Let them see the possibility and the light at the end of the tunnel. And the result is what we have today – a total change in the agency. So, I think that’s what Professor Bellamy referred to as a radical change; it means a sudden turnaround from negative to positive.

Ok, Sir, let’s talk in terms of the positives. Can we pick up some of the positives that speak in terms of your leadership and what the global picture is about NIMASA?

I will simply just mention a few. The first one is that, within such a short period, we changed the public perception of NIMASA. This we did working together with my colleagues. What used to be seen as the largely mediocre, non-performing government agency is now a respected regulatory and promotional agency, nationally and globally. Secondly, we reviewed the regulatory outcome trajectory, moved our focus from activities to outcomes and the results of reframing our objective showed within a short period. We are highly rated by our regional MOU as number one in port and flag state control, which is a core of our function. The third is that we changed the work ethic inside the Agency and it showed in the area of efficiency and effectiveness in delivering of our services. People imbibed a new culture; they are more sensitive, more efficient, and more effective because we built a knowledge-driven organisation. Aside from that, we re-engineered our contribution to the federal revenue purse; we increased that by 1,000%, in the four years we held sway.

What of employment we created by virtue of our work? For the first time, Nigeria placed more than 7,500 persons on board Cabotage vessels, we designed a solution to the cabotage challenge we were facing; what we called the 5-year waiver solution plan. We created new partnerships with the Nigeria Content Development Board (NCDB), including the universities; we created partnerships to drive cabotage. So I can go on and on about several results we’ve got from the strategic turnaround of the agency.

It would seem too that your change management approach, which you captured in your forthcoming book, has attracted the attention of such a leading maritime security scholar. Why did you choose a change management approach? What were the ingredients for its success that other government agencies can learn from?

We chose change management as a strategy because we needed to move the agency or the organisation in a different and positive direction. We wanted the agency to achieve a different result from what hitherto it was doing. That’s about change. But this is the change that needs to be done within a short period – a turnaround and not our normal reform and normal form of change management, but we adopted a number of change management principles, and I’ll just mention them. John Kotter’s 8 step management model; we also looked at the McKinsey’s 7 step change management model. We also examined works by several African scholars like Prof Don Baridam and Prof Dele Olowu. We adopted different elements from different models into our system because there was no model that fitted into our cultural and environmental context. In our cultural context, bureaucracy plays a key role; and secondly, politics is fickle. There are a lot of political interventions from the political arena in the regulatory world. Typically our cultural context does not emphasize efficiency and effectiveness in delivering of services. So, we looked at different change management models, and identified what is relevant to our environmental and cultural context. We unleashed a cocktail of these different models to create the kind of change that everybody is talking about in the agency. Moving in a new positive direction was my driving force. We sought to move the agency in a new direction because the old direction, in any case, did not enjoy the support and approval of both the appointing authority and stakeholders.

The notch is raised even higher with the description of your time at NIMASA as ‘successful high-level change management’. In the four years that you led this government agency, what shaped your approach and what determined your resource and people management stance?

What shaped our approach is that if NIMASA will command the respect of the industry, nationally, and globally, the industries need to see NIMASA in a new light. So, one of the things in our mind was that we wanted the industry, nationally and globally, to see the agency in a different light. NIMASA needed to command respect of the industry and stakeholders. It was our responsibility to create the right policy and fiscal environment for operators to deliver to the Nigerian people. We also realised that we cannot run a typical civil service bureaucratic organisation, [and] the reason is simple. The typical civil service bureaucratic organisation is actually a product of the British system, introduced and was not adapted to our environment. So, if you apply the principles, it is definite that it will not give you the kind of results you want. It’s not delivering the same outcome because that model was not designed for our culture. The British public service model was designed for a different kind of environment and culture.

The second thing we realized is that bureaucracy can stifle results. So, we needed to focus on homegrown solutions to make our agencies and organisations top-performing organizations as obtained in different climes. We simply wanted to exceed average or mediocre performance. Those were the driving factors. We also needed to reposition the organisation and earn the trust and support of stakeholders. We needed to deliver optimal performance and to do that we had to align our organization with the new vision and deliver values to stakeholders. So, if at the end of the day the maritime industry is not delivering value to the Nigerian people and stakeholders as an organisation, then we are not delivering on our mandate.

At the core of your leadership of the agency appears also to be a reformist agenda that helped you to attain the success that you achieved during your time at NIMASA. Can you share with us what was behind this radical reformist approach to your leadership of a government agency?

Alright, my understanding or my concept of strategic change means change that’s well-thought-through, envisioned, planned, designed and executed to take the organisation in a new direction, to deliver a different result and different value to stakeholders of the organisation. Now, what is unique about ours is that we did not follow the regular change process but we did what is called a “shock therapy” that was delivered in such a short period. And that’s the difference between a regular change management programme and a turnaround. The difference is that turnaround is achieved in such a short period. In change management, you have the latitude of time; but with the turnaround, positive results show positive effects within such a short period for the organisation to remain relevant so as not to lose value.

So, what is the focus of the organisation? Not losing respect band support of all key stakeholders. We needed to deliver results and value to Nigerian people. We needed people to trust us to protect that the interests of Nigerians by our work. So what did we do? We started with a diagnosis of the problem up to the point where we laid out a strategic plan; we executed a strategic turnaround plan; we reviewed it from time to time and tweaked anyone that needed to be tweaked.

And this is the same principle, within your business, whether in the government agency, non-profit or private sector whenever it is observed that you are delivering results optimally, you need to sit back and look at what is wrong. Why are we not delivering on the result? And to do that, you must look at different components of the organization. Organisations are made up of different sub-entities that come together for one common purpose. After the self-examination, you need to review your strategy from time to time to ensure that what you set out to achieve is what you are achieving and that the objectives you set up from point one is what is being accomplished . So, the approach should be a diagnosis of the problem, development of a plan, execution of the plan and a review of your executed plan to generate feedback which would help in designing a solution.

Still staying on the radical change and reforms, we are interested in this reformist agenda that helped you gain the success that you achieved in your leadership of the agency. Share with us what was behind this approach. Remember, this was a government agency that over time had lost its bearing.

Four key reasons why we adopted the radical reform approach. We were working in this sector that is private sector driven. The shipping industry is international by nature. Nobody’s going to measure you by Nigerian standard. There’s only one global standard. And so, if we are going to be competitive, we would be competing with other nations of the world; we cannot be competing with ourselves. Reason number one, we wanted to be competitive globally, and we cannot be competing globally by operating Nigerian standards. Secondly why do we need to reform? We realized in the 21st century, people have options; they will go to where services are best delivered. And so our competition is not local, our competition is international. We wanted to attract investors to our ecosystem, and to attract investors to our ecosystem, you needed to make the regulatory environment friendly, attractive, and efficient. We knew that our competitors are everywhere.

Also, we realized that even the people themselves in the agency will not give their best until they see us move in a new direction that will serve the greater interests of Nigeria. So, we wanted to motivate the people, make them see that there are possibilities. That way, they will give their cooperation and their support. And when they do, the import is that even the appointing authorities, who are representatives of Nigerian people, Mr. President, Minister of Transport; we will satisfy their yearning to see a regulatory agency that serves the interest of Nigerian people; we wanted to reposition the agency to serve the greater majority of Nigerian people; that was the third reason. The fourth is that we realized that the maritime sector has the potential to deliver to people -employment and create wealth. The sector can help us diversify the economy away from oil. And to do that, the regulatory agencies of that sector must be top-notch, efficient, cost-effective, and very forward-looking. Those are the four key reasons why we were reform minded. We also wanted the regulatory authority of the maritime sector to play her role well, and create wealth and employment for our people, and help diversify the economy. Those are the inspirational factors driving us and made us very passionate about reforming the agency, and my goal was to deliver on that self-giving challenge.

You spent four years leading a huge Nigerian agency with a primary focus on maritime security and safety, what were the crucial critical highlights during your leadership of NIMASA? And how did you deal with the challenges that you were confronted by?

One of the factors that helped us achieve our goal is teamwork. When we say teamwork? Team for me means working all stakeholders in the sector. We partnered with those that have a stake in the industry, and those truly committed to the progress of the industry. And I’m glad to say that they gave us their maximum cooperation. So, that’s one of the things that kept us in our reform agenda mode. Secondly, is the fact that we designed around specific initiatives. We didn’t try to reform everything. We identified and prioritized the areas that needed urgent attention. We designed based on human resources capabilities available for the challenge we set out to address. You know, we had to reset our human capacity and raise their level of energy. Maritime security was a key challenge and so we had to design a solution and our own response to the challenge of maritime security. Now, in the area of regulatory work, we reframed our focus from activity to measurable outcome. When we talk about teamwork that I spoke about earlier, it means everyone works from a common platform, common understanding, aligned around a common vision and common goals.

Of course, the third one is that we also worked with international community, when we realized that our work is not local in nature. It has an international dimension. So we got them to understand what we’re doing, to their buy-in in exchange for support. We needed them to align with what we are doing, and that’s the results that we’re all enjoying today.

We wanted you to highlight some of the critical moments in your four-year leadership. What would you put out, as the ‘I will not forget this’ moments during your time at NIMASA?

I will not forget when the federal executive council sat with all the ministers in attendance and singled out NIMASA and JAMB for commendation. The then Minister of Finance while addressing the press after FEC said, before now, you know how NIMASA was run, you know, how JAMB was run; today, the results are different. That’s one moment that the organisation was acknowledged as having moved in a new direction. Another moment is when 80 countries of the world gathered in Abuja to address maritime security, the challenge of maritime security. That day, the leadership of Nigeria was established as the regional leader in finding solutions to the challenges of maritime security. It was a moment that the world stood still for Nigeria. Three, was when the president assented to the anti-piracy bill and we became the first country in West and Central Africa to have a dedicated anti-piracy law. It was one moment that the nation lent or gave support to our key initiative; that made us proud. And of course, we have received a series of commendations from different international organizations including International Maritime Organization. Other industries stakeholders around the world also commended us.

Now, the other moment was when a number of Nigerian newspapers – Vanguard, The Nation and This Day – did an editorial on the reputation of the NIMASA; one of the newspapers said no other organisation in Nigeria has witnessed this type of reputation turnaround from negative to positive around the world as NIMASA did within a period of four years. That’s another moment that I’m very proud of and I cherish so much. Then, of course, another dimension of it is that because things were changing in Nigeria, the narrative in Nigeria was changing, we were invited to all centres to discuss maritime issues everywhere around the world. There’s nowhere we were left out. I’d like to talk about another one.

The day the maritime industry in Africa, elected Nigeria, as chair of the Association of African Maritime Administrators, AAMA. On that day we became the leader of maritime administrators in the continent of Africa. Those are some of the moments. I will not forget the annual celebration of our staff which we did for three years. We celebrated our staff publicly for excellence, excepted performance and innovative ideas. By celebrating them publicly we were encouraging our staff to be innovative, because if you’re not innovative as an organisation you will die. And as they were innovating, we were showcasing them to the world and it made them proud; encouraged more people; so we created an innovative ecosystem in the agency – a place people generate new ideas to solve problems.

Nigeria remains a major player in the maritime space on the west coast of Africa. How much success has been made in entrenching this and activating the capacity to maintain this position?

Well, we tried to institutionalize most of the initiatives we-started in the agency. We believe that those who succeeded us would advance it further. And I’m proud to say that a member of my team was selected by the government to succeed me. And that’s something anyone should be proud of. The man who used to be the Executive Director of finance and administration under my leadership was selected. And I believe that he is advancing our shared dream. One thing that we’re not able to complete was that I wanted to design a long term roadmap for the industry, to take the industry as a whole, not NIMASA, to the next level. We had started the process of designing it before we came to the end of my tenure.

I believe that we have already done preliminary studies and discovered the areas of strength; we did strength, weakness, opportunity and threat (SWOT) analysis. We are a nation of 200 million people; over 60 per cent of our people are below the age of 35 years. The import is that we have a young, educated and strong population, which can give the world a pool of seafarers. That is one area where we have strength. Now, the other area where we have strength is in cabotage because we have 857 kilometres of coastline and we have one of the longest inland waterways in Africa. So, how come we are not maximizing inland water transportation, why do we need to carry goods by road from Onitsha to Port Harcourt when we can do so by sea? Why do we need to carry goods from Markurdi by road to Aba when we can do that by sea? So, that’s another area of strength.

Then the other area is in technology components of shipping. You know, it’s not enough to have young people who are intelligent, who are smart; and so that’s one area we could have leveraged on. Then shipbuilding, you know, labour is cheap here, people are knowledgeable. We’re building capacity every day, but so far, so good; we don’t have a major shipbuilding activity in Nigeria. So those are areas we have identified and when we’re designing programmes on how to deliver on those areas, we believe that those who succeeded us will advance it to the next level.

There is also the importance that the Nigerian maritime sector holds in Africa and the world. You did your bit leading NIMASA, but how would you assess the state of the sector given the global pandemic? How much more needs to be done to position it as an economic power sector contributing to Nigeria’s GDP?

The sector faces a lot of challenges, from insecurity to lack of finance or funding, to lack of technical know-how to a hostile operating environment. Those are the key challenges. But the sector also has a lot of potentials. All we need is to harness this potential, design a solution around it and unleash the potential, and we will make the maritime sector the hub of an economic renaissance in Nigeria. And I mean the solutions are no rocket science. So, you know there are models that have worked elsewhere. All we need is to adapt it to our local situation, but the challenge is that the topmost echelons of government need to understand the numbers, they need to understand the number of jobs that can be created by the maritime sector, they need to understand the kind of wealth that can be and how taxation will benefit. They need to understand the potential of the sector in numbers. When they do, you can be sure that they will lend their support.

And I thought we started useful engagements, we had engagements with NNPC to change the terms of trade with respect to crude oil purchase and carriage; we had to engage with the Central Bank of Nigeria on the need to getting a single-digit interest rate fund, so that players can access it. We started engagements with the Minister of Finance and the tax authorities to review our tax system against or in favour of maritime players. We proposed a number of fiscal changes that need to take place for us to get a kind of ecosystem that will support the maritime sector. But unfortunately, we’re not able to take it to its logical conclusion. And I believe that those who will come after us will take it further.

From what you see and the players in the sector, what feedback are you getting, in terms of how the pandemic is shifting or shaping activities in the sector?

Oh, well, you know, the pandemic did not affect the sector adversely. What happened is that it fundamentally affected consumption patterns globally, one; now, for pandemic in Africa, [it affected] purchasing power. So in terms of import and export, people were consuming less, because they were not very active; whether in the energy sector, you are consuming less energy. So, we’re exporting less than we’re exporting before. Now, in the country here, we are also consuming less. So, we’re importing less into the country, and people were not very active. So whether in demand and supply sides, there’s a drop on supply-side and drop on the demand side. And in international business, shipping is a platform to move goods from one region of the world to the other. When there’s a drop in the demand and supply of goods and services, it naturally affects the sector. But the sector will remain relevant for as long as goods are being produced in one area and consumed at the other end of the world. Till the end of the world, the sector would remain relevant. So, indeed, the pandemic affected it imminently to the extent that shipping within that period did not deliver as much as anybody would expect. And of course, shipping dropped generally.

When you talk about indigenous participation, during your leadership of NIMASA, how much did you drive that and how do think this can be pushed forward?

Clearly, we identified participation of Nigerians in shipping as a major problem, and as an area we can maximize to create employment and wealth for our people One solution to achieve that, in any case, the over arching solution to that problem is to change the terms of trade from Free-on-board (FOB) to Cost – Insurance and Freight (CIF). We started that engagement with the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), the national oil comp in charge of crude sales and petroleum products sufficiency.

We had a series of sessions with them and it culminated in the setting up of the joint Technical Committee Incoterms to study and make recommendations to government. We provided the background knowledge, provided relevant data to show that Nigeria was losing billions of dollars and job opportunities by adopting the Free on Board terms of trade in sale of our crude oil. I believed we got listening ears of the top echelon of government. But, you know all these things take processes and time. But I’ve read in the papers lately that my successor is also pursuing that objective and that is commendable. I believe that’s something that is right, something that needs to be done. The reason is simple-if we’re able to change the terms of trade, it will create more employment for our people, more vessels would be engaged to create wealth for people; then we will be in control of the security implications of the lifting of crude. This competition to control that space has been on pre-independence-Nigeria. We have always had the struggle to control the transportation economics of moving oil around. With benefit of hindsight, I believe that we have laid the foundation and that our successors will achieve the result if they are single-minded and focused on it.

The cabotage funds are yet to be disbursed. Why do you think that has not been made despite being set up many years ago? Why has it been so difficult to get it done and how can it be unlocked?

It is most unfortunate that it happened and still happening. That is not the intention of the framers of the Cabotage Act. And I need to add that it is unacceptable. It is stifling development in the sector. And I believe it is caused by a combination of factors. One is politics. The second one is the lack of trust between stakeholders and those entrusted with responsibility of managing the fund. NIMASA as you are aware do not have the final authority to approve the disbursement of cabotage; that power lies with the Honourable Minister and I mean the various occupants of that position in time past, not the present one [Rotimi Amaechi]. We have had several ministers of transport before him. Though the current occupant of the office has taken steps towards the disbursement of the CVFF fund yet it has not materialized. Stakeholders believe that we are not taking steps to disburse and I hope that it materializes under his tenure so that at least Nigerians will understand that he meant well for the sector.

What was the motivation for you to write a book quickly after you left the government agency?

Books are usually inspired but I will highlight a few reasons why I documented my experience in NIMASA. The first, I wanted those who are serving in public office or who may be appointed in future to serve to learn from our failures and successes. The reason is that failure teaches a lot of lessons and can strengthen anyone to achieve amazing results. Secondly, I wanted to document our experience for posterity so history can record us. The third, we wanted to shore up the confidence of those in public office to believe in the fact that there are no odds that are insurmountable provided there is a will. NIMASA at the time we were appointed was almost an institution that was a liability, but today it is the toast of the nation. Fourth, we chose to put together a reference material or a workbook of sort so all those who want to embark on organisational renewal can see a model that worked to pick vital lessons from our experience. Finally, we applied principles of transformational leadership in a public sector setting and scholars of leadership will have lessons to learn from the way we applied the principles.

What are some of the unique features of the book?

Strategic turnaround brings a lot of insight to what is unique about managing a public sector organisation in a Third World country where bureaucracy is stifling and politics can derail the best of initiatives. The book is presented in the form of a story to show that European model of public service system without adaptation to our local setting will have difficulty delivering the results we expect. Our cultural context and environment are unique so when we import leadership and management principles we should adapt it to our situation. We magnified what Peter Drucker said that you don’t manage what you don’t measure. Our emphasis in the NIMASA journey was get to the root of the problem, we called that diagnosis, then set goals to achieve desired results and the second is performance measurement at every unit of the organisation and at the organisation wide level. We used a lot of stories or narratives to show the importance of quantitative and qualitative measurement of outcome. Finally we used a good number of African folklore to show that a lot of leadership and management principles are embedded in our African stories.

You propose a 6-city leadership coaching tour in June 2020 to get a team to teach transformational leadership based on the book. What inspired this?

My Publishers and handlers consulted and came up with the programme and fixed it for June 2021. Though, I have already scheduled speaking engagements outside Nigeria in January, March and April 2021. There were other factors that my publishers and handlers put into consideration before arriving at June 2021. It is not the usual book reading tour but leadership coaching clinics based on principles embedded in the book. It is purely an initiative of my publishers and marketing company.

How long did it take you to write this book?

Oh, literally it took me the last eight – nine months. I have always had the idea but I paid serious attention to it after I left office and I was able to sit back and reflect on my time at the Agency.

What areas in the maritime sector, now that you can take some steps back, with a helicopter view, that you think that Nigeria needs to pay serious attention in its quest to diversify the economy?

There are four major areas Nigeria should pay attention to. One is that our operating environment does not support innovation, entrepreneurship and productivity. So, the moment you set up a business here the hostile environment kills that initiative. The second one is lack of infrastructure. The third is the issue of security or insecurity, there is a sense of being unsafe everywhere in the country. The government needs to address that to give people confidence. Now, cost of finance does not make us competitive, nobody can go and borrow money at 22- 25 per cent interstate rate and expect to survive in this country. Finally, our education system is geared towards preparing people for the world of work, not for the world of creating businesses. So, we need to look at our curriculum again.

How do you stimulate innovation? How do you create entrepreneurs, those who will create jobs, not those who have been trained to go and work in Shell or the Civil Service? So, these five points are pain points that deserve attention.

You were hailed by Professor Chris Bellamy to have radically reformed NIMASA, which is captured in your forthcoming book – Strategic Turnaround. What do you make of it and what do you hope to see happening now in the agency you once managed, and the maritime sector going forward?

I’d like to see an agency that is more reform-minded, and I want to see other government agencies become more reform-minded, become more innovative. I like to see that. And I like to see the maritime industry take its rightful place in the order of economic priorities of the government. I like to see a government that takes maritime sector as a priority sector that has capability and capacity to create employment and wealth. I like to also see the international community take us more seriously in the maritime sector because we have something to offer

Finally, I want you to answer this one later which is, where next for you? Rivers State is still there and you have distinguished yourself as a management person. I want you to share with us what Dakuku Peterside management style was, as somebody who had the private sector thinking in a government agency?

I’ve heard different media organisations describe me as a transformational leader. Some say, I’m a turnaround management expert and others say I am a leadership Coach. I’ve heard all of these sobriquets. But the one I prefer most is team player who can deliver unusual results working with others. And if you ask me, my management style is to coach and collaborate with others to find solutions to problems that others consider impossible to solve.

For me, I believe in possibilities, I believe that everything is possible, depending on the energy and the intellect you put into it.

Well, you know, that power belongs to God. But we all must also have human plans which God will bless. For next year, I already have about seven major speaking engagements around the world, in China, in Egypt, Kenya, and United Kingdom. Starting from Egypt, in January, in Kenya, in the UK, amongst others. I’ll be speaking around the world, on transformational leadership, Maritme, regulatory relationships while doing business in Africa. And in the area of politics, I’m yet to make up my mind, on what new project I like to pursue. But again, man, by nature, is a political animal. So it is not easy to say I’ve shut that door. Nobody, I don’t think anybody can freely say so.

Are you not tempted to dive into the private sector given your experience in NIMASA where you operated more like a private sector leader in a public institution?

The temptation is there, I will not deny it, you know, between public service, which will not give you money and operating in the private sector where you make money, there’s the attraction you cannot just wish away. But early in life for me, at the age of 11, I identified my calling, which is service to the public; impactful leadership. Leadership that will help people get fulfilled. That’s the area that I believe I’m called to serve, I’m not called to make money for myself. I think I’m relatively comfortable, by the special grace and favour of God. Mine is to help others succeed and achieve their own goals and objectives. In helping others achieve their dreams I will be fulfilling mine. Thank you very much.