Africa’s corn harvest this year is a tale of two extremes as worries about overflowing silos and rotting crops in the south contrast with the east where supermarkets are running short of the staple food.

Zambia and South Africa are both predicting record output of the grain, while Zimbabwe may meet its domestic needs for the first time since it began seizing land from white farmers in 2000. Yet in East Africa, 17 million people may be facing hunge, and concerns about food shortages are driving up prices as governments scramble to secure imports.

“It all comes down to weather,” said Wessel Lemmer, a senior agricultural economist at Barclays Africa Group Ltd.’s Absa unit in Johannesburg. “There’s usually an inverse relationship between rainfall in south and East Africa but this year has been more at the extreme end of that cycle.”

Volatile weather conditions, prompted by the 2015-16 El Nino weather pattern and exacerbated by climate change, have caused extremes of drought and heavy rain across sub-Saharan Africa. The resulting variations in crop yields are stretching the continent’s storage capacity and transport links while highlighting cross-border trade barriers that make it difficult for food to get where it’s most needed.

Local Politics

“Transport costs, import-export bans, restrictions on genetically modified grain and local politics all hinder trade,” said Jacques Pienaar, a Bloemfontein, South Africa-based analyst at Commodity Insight Africa. “In Africa, you can only move so much produce.”

Corn, or maize as it’s called locally, is a central part of life across much of sub-Saharan Africa, usually ground and mixed with water to form a porridge or stiff dough. It’s called pap in South Africa, sadza in Zimbabwe and ugali in Kenya.

Kenya’s reserves of corn dropped to less than a day’s worth of consumption earlier this month, with annual food inflation reaching 21 percent in April, squeezing a country where almost half of the population live on less than $2 a day. The government is planning to import 450,000 tons of the grain to plug the deficit and is subsidizing supplies.

Yet imports from South Africa, the continent’s top producer, are unlikely because Kenya, like most African countries, doesn’t allow genetically modified corn, according to Wandile Sihlobo, an economist at the Pretoria-based Agricultural Business Chamber. About 85 percent of South Africa’s corn is GMO, he said.

Record Crop

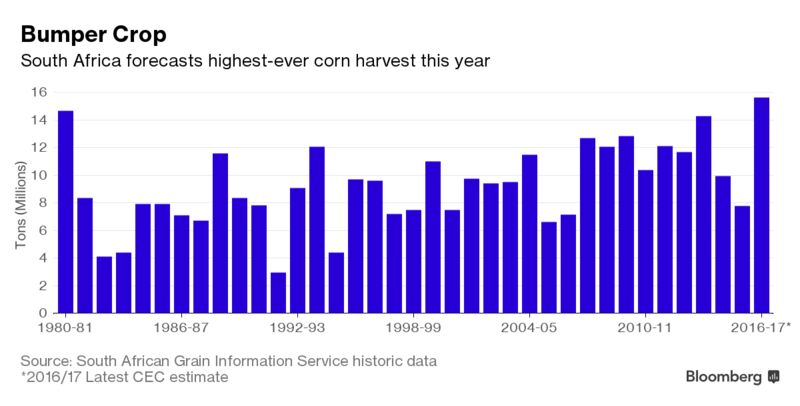

South Africa said Friday it expects to reap an unprecedented 15.63 million metric tons this year, after rains during the prime growing period helped farmers rebound from the worst drought in more than a century.

White corn for July delivery dropped to 1,652.60 rand a ton, the lowest for a most-active contract in three years, in Johannesburg on Monday before rebounding to 1,729 rand a ton.

For Zambia, which this month lifted a corn-export ban after forecasting a record 3.6 million-ton crop, the biggest question is where to put it all. The country only has storage capacity of about 2.2 million tons, according to the Grain Traders Association, and with neighbors Zimbabwe and Malawi already well-supplied, landlocked Zambia’s export options are limited and costly.

“South Africa will easily outweigh us in terms of transportation,” Chambuleni Simwinga, the association’s executive director, said in an interview. All indications point to “a crisis in terms of wastage,” he said. Zimbabwe is also facing a severe lack of storage.

In addition to African neighbors, South Africa is eyeing nations including Japan, Taiwan and South Korea as buyers for its estimated 3.6 million-ton surplus this year, according to producers’ group Grain SA. The government is also considering a strategic grain reserve to supplement harvests during lean years, Agriculture Minister Senzeni Zokwana said.

The country’s preference for white corn, which will account for about 60 percent of South Africa’s output this year, will make it doubly hard for the country to find international markets for all of its surplus, Sihlobo said.

“Yellow maize will easily find market in the world, while white-maize exports might find low or soft demand,” he said.