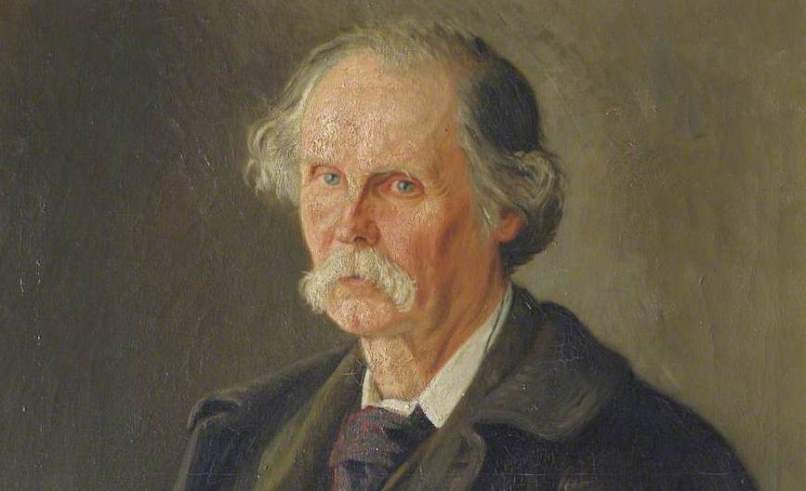

Before Alfred Marshall, economics was a study at the service of government; it was a tool designed to help understand how to regulate income and determine prices of labour and other factors of production as well as the product of production in a bid to increase the wealth of nations. In that context, one can easily see why the descriptive term “Political Economy” was hence more than apt. In a total break away from the dominant idea and tradition of focusing economics on the study of wealth and production as part of the moral, political and religious elements that govern societies, Alfred Marshall led the idea of positioning economics as the study of how human beings meet their needs: A total refoundation of economics as a study.

As part of his effort and success in refounding economics, Alfred Marshall conceived and described economics as “a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life; it examines that part of individual and social action which is most closely connected with the attainment and with the use of material requisites of well-being. Thus, it is on the one side a study of wealth and on the other and more important side, a part of the study of man.”

With this revolutionary articulation, Alfred Marshall added three crucial elements to our understanding of economics. Firstly, he was able to turn economics into a study that not only emphasises the anthropocentrism of economics but he also makes it a study of the common or average man. Not the producer, not the labourer, nor the entrepreneur or the landowner but just the individual. In his new conception, he underlined the strands in economics and he prioritised one: Alfred Marshall acknowledged that economics is also about wealth creation (macroeconomics), but he also states what he thinks should be priority: microeconomics, which he described as “the other and more important side.” Thirdly, he establishes economics as a discipline that, by using scientific tools, allows us to study human beings in the process of conducting their affairs, not the way we study animals, plants or objects: A social science.

More than anyone else, the economic social scientist, Alfred Marshall, moved us away from the simplistic take on economic issues by pointing out that the factors affecting an economic object of study or occurrence are too numerous and too complex to be totally and completely studied to come to a single and final solution. He argued that the best way was to focus on some variables of the object of study (the most obvious and relevant factors), whilst keeping the other variables inactive: “Keeping other variables constant”. This method allowed Alfred Marshall to introduce us to his concept of partial equilibrium where we are shown a key principle in economic studies: the ceteris paribus principle. And whilst at it, as a corollary of keeping all things equal, he also introduced us to two kinds of isolations: Hypothetical and Substantive isolations.

General education owes and rightly gives credit to Alfred Marshall for two major contributions in the study and teaching of price, demand and supply. One is his very famous “supply and demand curve” that shows us the point at which the market is in equilibrium. Few people have passed through school without seeing that curve in textbooks and on boards; so sadly, we shall not be reproducing it here. A now successful business manager once confessed to me that her first problem with, and an unending passion for, economics was ignited by the supply and demand curve.

The other major contribution Alfred Marshall is known for is his original concept of price elasticity of demand. For a long time, it was taught and agreed that the demand for any product or service will decrease if the price of such product or service increases. It was Alfred Marshall that brought it to our attention that assumed automatic and universal negative correlation between price and demand was not always valid rather the correlation was all subjective and variable. For Alfred Marshall, there is an inseparable and complex connection between cost of production, supply, demand and price elasticity. The Marshall notion of price elasticity showed us that the prices of some kinds of goods and services can very well increase without a corresponding fall in their demand. In such cases we are dealing with goods and services with inelastic prices. Goods and services with inelastic prices tend to be those that we consider essential to our lives, such as energy, health related goods and services, or things we are addicted to.

We must add here that a product or service will be more or less elastic depending on the consumer and the market. The price of fizzy drinks will affect the demand of a consumer addicted to that drink in a different way from the way it would a consumer who is not addicted. Prices of diamonds will tend to be very elastic as most can defer or even cancel buying them at all. Alfred Marshall himself defined elasticity of demand as the percentage change in quantity demanded to the percentage change in price. He identified five grades of elasticity: absolutely elastic, highly elastic, elastic, less elastic and inelastic.

Alfred Marshall’s principal publication was his ‘Principles of Economics’; it was first published in 1890 and it became the first textbook of economics. In introducing that book, he gave us another insight on what he thought economics should be and how he thought it would evolve into, by telling us that “Economic conditions are constantly changing, and each generation looks at its own problems in its own way… Economic studies are being more vigorously pursued now than ever before; but all this activity has only shown more clearly that Economic science is, and must be, one of slow and continuous growth. Some of the best work of the present generation has indeed appeared at first sight to be antagonistic to that of earlier writers; but when it has had time to settle down into its proper place, and its rough edges have been worn away, it has been found to involve no real breach of continuity in the development of the science. The new doctrines have supplemented the older, have extended, developed, and sometimes corrected them, and often have given them a different tone by a new distribution of emphasis; but very seldom have subverted them.”

He then informed us that his own contribution is “an attempt to present a modern version of old doctrines with the aid of the new work, and with reference to the new problems…”

Join me if you can @anthonykila to continue these conversations.

ANTHONY KILA

Anthony Kila is a Jean Monnet professor of Strategy and Development. He is currently Centre Director at CIAPS; the Centre for International Advanced and Professional Studies, Lagos, Nigeria. He is a regular commentator on the BBC and he works with various organisations on International Development projects across Europe, Africa and the USA. He tweets @anthonykila, and can be reached at anthonykila@ciaps.org

business a.m. commits to publishing a diversity of views, opinions and comments. It, therefore, welcomes your reaction to this and any of our articles via email: comment@businessamlive.com