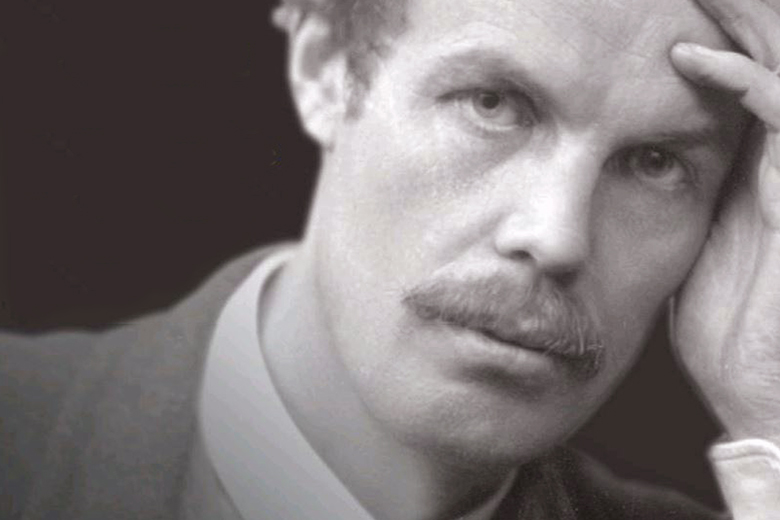

BY ANTHONY KILA

In the secular world, there are very few personalities or thinkers able to combine the feat of getting fame and respect amongst other thinkers and teachers of their time and those that come after them, while declaring themselves as total devotees and apostles of another thinker or teacher. As scholars, such personalities profess to do nothing else or more than explaining and implementing the thoughts of their teacher. One of such scholars is Arthur Cecil Pigou and his teacher, Alfred Marshall.

A.C Pigou believed that Alfred Marshall had done and explained all that needed to be known in economics and he taught the same to his students.

Those who met him at Cambridge and those that came years after he had left, remember and mimic his famous catch phrase: “It is all in Marshall.” So much was his faith in Marshall and his belief that Alfred Marshall’s teaching, especially as laid out in the “Principles of Economics”, is so all-embracing and defining, that A.C Pigou himself wrote that: “The first time one reads the Principles one is very apt to think it is all perfectly obvious. The second time one has glimpses of the fact that one does not understand it at all. … When one discovers that one did not really know beforehand everything that Marshall has to say, one has taken the first step towards becoming an economist!”

Arthur Cecil Pigou was by all accounts a brilliant scholar and an amazing teacher. He presented himself and his thoughts with impeccable oratory skills and his writings were clear, logical and instructive. Many of his own students also went on to become great economists and hold important chairs in their own right.

A.C Pigou was born in November 1877 and even from an early age his brilliance did not go unnoticed. He went from scholarship to scholarship and medal after medal; then he found his way to Cambridge to study History, Philosophy and Ethics. During his Cambridge days, he took time to become President of the Cambridge Union. It is safe to say A.C Pigou bumbled into Economics, then taught by Alfred Marshall, and fell in love with it. So much was his dedication that he quickly won the Adam Smith Prize.

As an economist A.C Pigou was moulded as a scholar whose idea should help solve the problem of the world. He was one of those men that Alfred Marshall hoped and worked to prepare so that they could enter the “world with cool heads but warm hearts, willing to give some, at least, of their best powers to grappling with the social suffering around them…”. It is therefore no surprise that Pigou’s major work was his, “The Economics of Welfare”. Whilst remaining an economist of the classic school that embraced the free market and left the choice of production to private judgement, like the rest of Cambridge, A.C Pigou was interested in a fairer society for all. What a joy it must have been for Alfred Marshall to see his own creation (Arthur Cecil Pigou) elected, before and above others, to take over his chair in 1908.

More than anyone, it was Arthur Cecil Pigou that first articulated the Marshallian notion of externalities to us in economics and politics, and with that, becoming the first environmental economist. In his signature brilliant way, A.C Pigou articulated that in the process of production and other activities that individuals and groups carry out, there are some effects that arise for individuals and groups that are not part of the process of production and other activities of the active participants. He classified the positive effects as benefits and classified the negative effects as costs.

An example of the positive effect (externality benefit) will be the advantage of living around a company that produces at night and lights its compound in a way that those living near the company also get light in their own compound; or a person living next to a bakery that gets to enjoy the fragrance of pastries. An example of a negative effect (externality cost) will be the adverse effect of air pollution that the society incurs from the making and using of motor vehicles, or the effect of water pollution that the oil and gas industry creates in the communities where they operate.

For the externality benefits, A.C Pigou recommended subsidies as a form of reward and encouragement for those whose activities provided benefits for the rest of the society. His reformulation of the concept of subsidies will then allow him to propose later, that in instances of unemployment, due to lack of demand for products and services, and therefore for labour; or where employers are hesitant to employ some part of the society (like women and veterans in his own time), the government can subsidise employers, like manufacturers, whose products will benefit all and whose process will create employment.

For negative externalities, A.C Pigou argued that the market, left to its own devices, could not solve the problem of the added and unintended cost that some activities can and tend to generate. He proposed a collective and deliberate solution: Taxation. With this concept, individuals and organisations engaging in activities that provoke adverse effects for the society will be considered liable for causing externality costs and be taxable for their activities. The tax to be paid has been named Pigouvian Tax after Arthur Cecil Pigou, and it is the foundation of taxes like, the green tax or carbon tax; and the tax on cigarette production and consumption.

A very original and now topical thought that A.C Pigou’s concern and commitment to welfare led him to is his intuition and position on intergenerational fairness. Pigou called our attention to the need of the present generation to be mindful of those that will come after us and consequently be strategic in how we spend the resources of today. He thought it would be better to employ a collective solution and he proposed that, “(…) the State should protect the interests of the future in some degree against the effects of our irrational discounting and of our preference for ourselves over our descendants.” Amazingly, too many do not remember to cite Pigou when they make the case against using the environment without thinking of posterity, or spending as if there is no tomorrow, and yet, starting from Arthur Cecil Pigou would make more than a bit of difference when making such cases.

-

business a.m. commits to publishing a diversity of views, opinions and comments. It, therefore, welcomes your reaction to this and any of our articles via email: comment@businessamlive.com