After more than a year as both creative director and chief executive officer of Burberry Group Plc, Christopher Bailey was tired of the juggling act. So in the autumn of 2015 he asked the board to let him hire someone to assist in running the business. He soon realized he didn’t just need a helping hand. He wanted someone to take over as CEO.

A few months later, Bailey met with Marco Gobbetti, CEO of Celine, a label owned by luxury conglomerate LVMH whose sales have boomed on the back of its cult handbags. They met in London for what was scheduled to be simply breakfast and ended up talking for hours about Burberry’s future. Gobbetti—a cheerful 57-year-old Italian—soon agreed to take over as Burberry’s CEO, leaving Bailey, 46, to concentrate on design. “We will work hand in hand,” Bailey told Bloomberg TV when Gobbetti’s appointment was announced last summer. “It wasn’t a big decision for me whether I had a CEO title or not.”

Gobbetti, who spent the past six months as Burberry’s interim executive chairman for Asia, will assume the CEO post on July 5, working alongside Bailey. That could set up one of fashion’s great partnerships—think Tom Ford and Domenico de Sole at Gucci in the 1990s—or a clash over who’s in charge, reminiscent of Ralph Lauren when the founder hired Stefan Larsson as CEO, only to see him quit last winter less than two years into the job after the two butted heads over strategy.

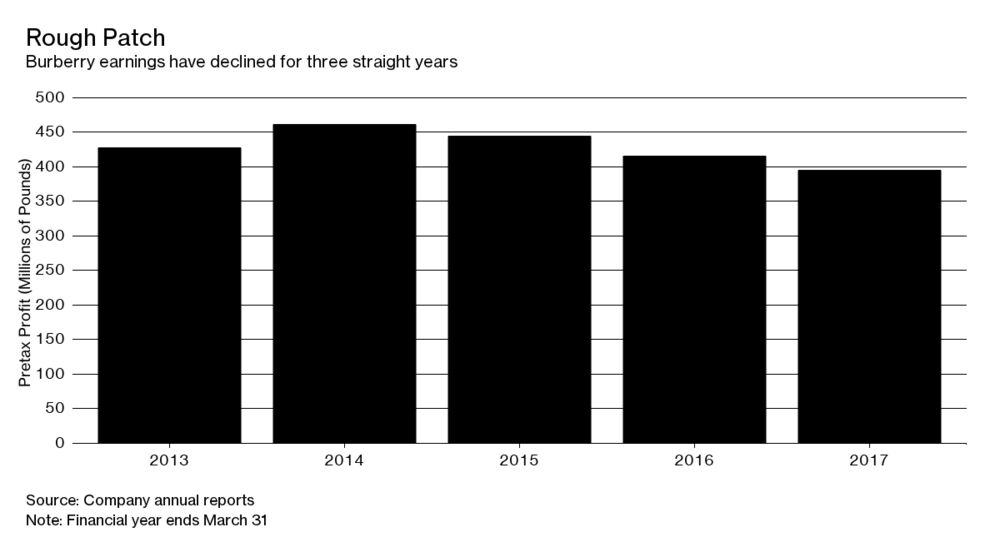

As Bailey took the helm, rising economic uncertainty and a crackdown on corruption in China were putting the brakes on luxury spending. After three consecutive years of declining profits, Burberry is struggling to define its place in the business. Kering, the owner of Gucci and Saint Laurent, saw sales surge 30 percent in the first quarter while Burberry’s climbed only 2 percent.

With 2016 sales of 2.8 billion pounds ($3.6 billion), Burberry is about the size of Prada but half as big as Ralph Lauren and a minnow when compared with French groups Kering and LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE. Takeover speculation surged last winter when 91-year-old Belgian billionaire Albert Frere, a long-time associate of LVMH CEO Bernard Arnault, bought 3 percent of Burberry’s shares. Frere declined to comment.

Gobbetti, who spent a dozen years at LVMH, isn’t an obvious choice to run a quintessentially British brand like Burberry. Founded in 1856 by Thomas Burberry, who designed waterproof gabardine “trench” coats worn by British soldiers in World War I, Burberry is the most famous British heritage brand in a sea of French and Italian labels.

Burberry’s black-tan-red plaid, used in the linings of trenchcoats and myriad other products, is immediately recognizable but retains the stigma of the 1990s when it was used on everything from dog leashes to baseball caps, tarnishing the company’s luxury image. Under Bailey’s guidance, Burberry has sought to restore its luster by reining in the plaid.

Bailey has told colleagues he never really wanted the CEO job, raising hopes that his return to full-time design might trigger a creative reawakening. He’s already working with fresh talent: Handbag designer Sabrina Bonesi and merchandising director Judy Collinson joined from Christian Dior this year. “Bailey seems genuinely enthusiastic about the ability to concentrate on his creative work,” says Justine Picardie, U.K. editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar. “The two collections he’s done since the decision to bring in Gobbetti have been very strong.”

But Erwan Rambourg, a luxury analyst at HSBC, says Burberry has become “a bit stale” and might benefit from a more thorough overhaul. “We have nothing against Christopher Bailey,” Rambourg says. “But if you’re writing the next big chapter for the brand you need a design shakeup.”

One concern is that Burberry has lost focus. Its website offers everything from $33,000 alligator-skin bags to $105 t-shirts. In the past year, Bailey has tried to make the company’s line-up more coherent by merging its three sub-brands—the Prorsum catwalk collection, the classic Burberry London, and the youth-oriented Burberry Brit—into a single label and scaling back the brand’s retail footprint.

Gobbetti has a reputation for reviving wayward labels via amicable partnerships with star designers—Phoebe Philo at Celine and Ricardo Tisci at Givenchy—a good omen for his relationship with Bailey. They may, however, differ over digital strategy. At Celine, Gobbetti resisted e-commerce, worried it might lead to overexposure. Burberry, by contrast, was quick to embrace the internet, streaming runway shows and building a social media following of more than 48 million.

“It’s ironic but brave that someone who had been running a business that was violently anti-digital and e-commerce is going to a business that promotes itself as being at the forefront of everything technological,” says Hugh Devlin, a lawyer advising fashion brands at Withers Worldwide in London.

If Gobbetti’s management of Celine is any guide, Burberry could continue to see lower profits as he seeks to boost the brand’s cachet. He temporarily closed Celine’s costly shop on Manhattan’s Madison Avenue and refused to supply department stores with enough ‘it’ bags to keep up with surging demand, says Ron Frasch, a former president of Saks Fifth Avenue and a long-time friend of Gobbetti. The idea: create scarcity and thereby exclusivity. “We were frustrated. How could he not sell to us?” Frasch recalls. “He didn’t take the short-term benefit and instead tried to really build a brand for the long term.”

Burberry’s turnaround could be slow as Gobbetti and Bailey look for the right balance between luxury and mass-market appeal. One morning in June, Burberry’s 44,000-square-foot flagship on London’s Regent Street was eerily quiet, with just a handful of Chinese tourists, trying on trench coats and makeup, vastly outnumbered by black-clad salespeople clutching iPads. Burberry is “accessible,” says Jin Jin, a 23-year-old Chinese student buying sunglasses and a tie for her father. “I can’t afford a Dior handbag,” she says, “but I can shop here.”

Courtesy Bloomberg