Kenya’s central bank is taking an unusual (intimidation) approach to protecting its currency.

According to Bloomberg’s report, monetary authorities in Nairobi have been cracking down on selling, hedging and even making bearish predictions, according to traders and analysts. In a sign of the skittishness, none of 12 market participants contacted by Bloomberg spoke on the record, citing possible retaliation.

“There’s a hush-hush rule on traders: Either talk up the shilling or shut up,” said Kwame Owino, chief executive officer of the Institute of Economic Affairs, an independent research institute based in Nairobi that tracks Kenyan economic policy and financial markets. “This kind of pressure isn’t sustainable, especially when you have an open trading system. It will end in tears.”

So far, Kenya has dodged years of emerging-market currency turmoil that forced Egypt to surrender control of its pound, sparked a hard-currency shortage in Nigeria and pushed South Africa’s rand to all-time lows. A concern is mounting among analysts that violence could follow Tuesday’s elections and trigger a depreciation that would lead to a debt crisis, according to two Nairobi-based traders who declined to be identified.

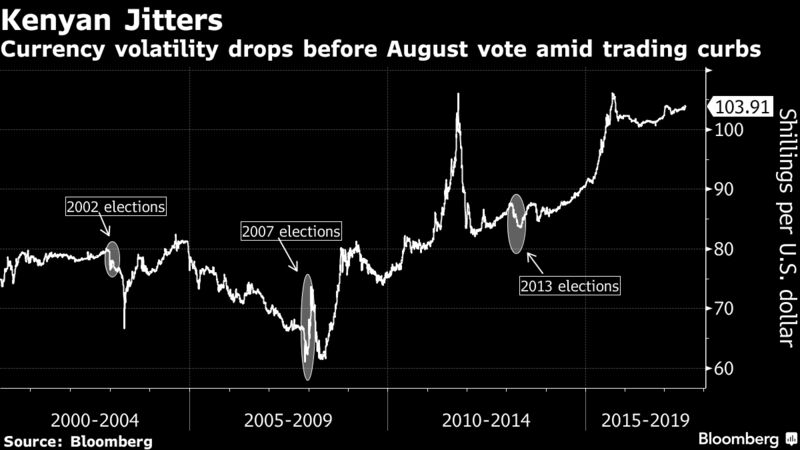

The shilling is officially a free-floating currency, but it’s barely budged for months, with volatility falling to a third of the average for the benchmark emerging-market currency index last month. Traders say Yale University-educated central bank Governor Patrick Njoroge, in his post for two years, and deputy Sheila M’Mbijjewe have made their desires clear that traders shouldn’t speculate.

The central bank didn’t respond to emailed questions about the traders’ claims. Njoroge told reporters in Nairobi last month that while the bank intervenes to manage volatility, it doesn’t target a specific level for the currency.

Still, some traders shared stories of being summoned, along with their bosses, to the central bank headquarters in Nairobi and getting reprimanded for publicly speaking about possible shilling weakness or for conducting trades that might hurt the currency. The traders said they are keeping a low profile to avoid putting their jobs at risk because their bosses don’t want to attract the wrath of the central bank.

For instance, they said the central bank is asking local banks to justify all hedging contracts arranged for clients wanting protection against future shilling declines. To avoid the hassle, some exporters are opting not to take any protection at all, three traders said.

In addition, the central bank in June banned the 80,000 Kenyans who trade currencies via online platforms from conducting transactions involving the shilling, the Capital Markets Authority said June 20. A separate directive from the central bank has delayed the planned introduction of derivatives — like currency and equity-index futures — to make sure they wouldn’t hurt the exchange rate, according to the Nairobi Securities Exchange.

‘Little Room’

“They want to ensure there is little room for traders to manipulate the market,” said Bernard Omenda, who resigned last year as head of treasury at Nairobi-based lender Spire Bank. He now runs Meta Capital Ltd., which offers technology including automated trading systems. Banks need to take swift steps to offset their currency exposure, such as investing in fixed-income securities, he said.

Treasury chiefs at Kenya’s biggest banks, including KCB Group Ltd., Equity Group Holdings Ltd. and Co-operative Bank of Kenya Ltd., declined to comment. Commercial Bank of Africa Ltd.’s head of treasury, Raphael Owino, said he wasn’t aware of any central bank directives.

So far, the central bank’s tactics are working. In the past year, the shilling weakened 2.4 percent to almost 104 per dollar. That compares with losses of 6.4 percent in neighboring Uganda, a retreat of 9.5 percent in Ghana, and the Egyptian pound’s 50 percent slump.

There’s a lot at stake for the East African nation of 47 million people if the shilling weakens sharply. Rising import costs would thrust inflation back into double digits and make it harder to service an external debt burden that doubled in four years to almost $21 billion. It would also threaten the nation’s $7.5 billion of reserves which, while near a record, cover just five months of imports.

Debt Costs

A weaker shilling would also drive up foreign-debt costs. The first repayment on $2.75 billion of Eurobonds sold in 2014 is due in the fiscal year that begins on July 1, 2018, which will lift the government’s external-debt repayments to 232 billion shillings ($2.2 billion) by 2018-19 from 43.6 billion shillings in the fiscal year that ended June 30.

On the flip side, artificially propping up the currency diminishes the competitiveness of the black-tea exporters and flower growers who rely on business abroad for their roses and lilies.

Treasury Secretary Henry Rotich said Kenya’s debt, estimated by the International Monetary Fund at 54 percent of gross domestic product last year, is “sustainable” and only a sharp depreciation in the currency would alter that view.

“If the shilling depreciated by a huge margin, it would impact on debt repayments,” Rotich said in a July 31 phone interview. “But for us, it is a significant depreciation that will have an impact and by significant, I mean by a magnitude of 20 percent. If the dollar goes beyond 120 shillings, for example, that is when it will have a big impact on our debt.”

The central bank cited medium-term budget strategy documents published on the Treasury’s website when it said by email on Monday that “Kenya faces a low risk of external debt distress,” even in the event of a “significant depreciation of the exchange rate.”

Devaluation Pressures

If recent history is a guide, emerging nations can’t withstand devaluation pressures for long. Since 2014, as China weakened its yuan and oil prices dropped, countries from Argentina to Kazakhstan abandoned dollar pegs, and Egypt followed in November after initially resisting. Nigeria, where street vendors charge a 14 percent premium for dollars, is under pressure to do the same.

Kenya, on the contrary, has tightened currency controls since a 2011 crash wiped out a quarter of the shilling’s value, dragging it to a record 106.75 per dollar. Policy makers at the time blamed speculators, but investors said the sell-off was warranted as a fierce drought caused Kenya’s widest current-account deficit ratio since 1999.

More recently, Governor Njoroge targeted speculators as the shilling inched downward in the final weeks of a tight presidential campaign that pitted incumbent Uhuru Kenyatta against former Prime Minister Raila Odinga. While the vote four years ago passed relatively peacefully, more than 1,100 people were killed in turmoil sparked by a disputed 2007 result. If Kenyans suspect the latest ballot is rigged, analysts say it could happen again.

Chill Out

“There is a lot of speculation from people who think things will go haywire,” Njoroge said July 18, assuring the bank would dip into foreign reserves to defend the currency. “Those people need to chill.”

Shortly after taking office in 2015, Njoroge barred Kenyan banks from keeping more than 10 percent of core capital in open foreign-currency positions, down from a 20 percent ceiling.

The trading crackdown intensified after the shilling suffered its biggest monthly loss since 2015 in January, falling 1.3 percent. The central bank started scrutinizing trades, often grilling bank treasurers for having open positions much smaller than regulatory limits, traders said.

Since then, three-month shilling price swings have fallen to 1.2 percent, near the lowest since Bloomberg started collecting data 30 years ago. Only four of the 10 analysts who typically give currency forecasts on Bloomberg, meanwhile, currently provide market outlooks.

Not everyone feels silenced. Charlie Robertson, the London-based global chief economist at Renaissance Capital, which has offices in Nairobi, put the shilling’s fair value at 124 per dollar, 16 percent below current levels, with projected declines to 109 by year-end and 114 the following December.

Sharing Models

Robertson said the central bank has asked his colleague, Yvonne Mhango, who oversees sub-Saharan Africa, to share her foreign-exchange model for “reassurance” that the market outlook was justified. He added that the request is understandable for a frontier market. “The central bank seems determined to prevent ‘finger in the air’ forecasts being touted around, which might be used to sharply move the exchange rate,” Robertson said.

Owino at the Institute of Economic Affairs said intimidation tactics will backfire. He said a black market could develop, although initially, Kenyans may buy dollars from neighboring countries like Uganda, where the currency market is freer. In a sign foreign investors are jittery, outflows from Nairobi stocks reached a two-year high in the second quarter, Standard Investment Bank data show.

“What we need to ask ourselves is this: Will this escalate into a crisis and will that crisis lead to a very big slide? I fear that is what will happen,” Owino said.