Meeting the challenge of gas as Africa’s transition fuel

July 10, 2023937 views0 comments

BY PAUL DOZIE ARINZE, Ph.D.

Paul Dozie Arinze, who holds a doctorate in business administration and is the president of Pedestal Africa Limited, is an entrepreneur, corporate executive, investor and author, with wide ranging experience in energy, business strategy, public policy, and international law. He has special interest in the interaction of investment, regulation, and policy in emerging economies, especially Africa, and can be reached via comment@businessamlive.com.

Read Also:

Africa is currently locked with the global energy system in an intense debate about what role Africa’s vast gas resources should play in the global energy transition. Beyond that, is the wider question about what comes first – development or transition.

The West-led industrialised world is leading the argument that, with the risk of irreversible rise in global temperatures, and the disaster it could bring, the world must roll back the use of carbon emitting fuels, including natural gas. Instead, everyone must embrace greener alternatives like solar and wind, and any investment in extractive hydrocarbons must increasingly be short term.

John Kerry, US climate ambassador and former secretary of state, is leading the charge in this line of argument. He recently toured Africa spreading a warning: even if gas were to serve as a transition fuel for Africa, any investment with a time horizon beyond ten years would not be viable and should be abandoned. To African environment ministers gathered in Senegal last September he said: “We are not saying no gas. (But) we do not have to rush to go backward, we need to be very careful about exactly how much we are going to deploy, how it is going to be paid for, over what period of time and how do you capture the emissions.”

John Kerry, US climate ambassador and former secretary of state, is leading the charge in this line of argument. He recently toured Africa spreading a warning: even if gas were to serve as a transition fuel for Africa, any investment with a time horizon beyond ten years would not be viable and should be abandoned. To African environment ministers gathered in Senegal last September he said: “We are not saying no gas. (But) we do not have to rush to go backward, we need to be very careful about exactly how much we are going to deploy, how it is going to be paid for, over what period of time and how do you capture the emissions.”

Yet, it’s not just one voice that is calling for the commercialisation of Africa’s 625 tcf gas reserves in fast, before it’s timed out by the transition to lower carbon fuels. A World Economic Forum report in 2021 sums it up, quoting Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency: “If we make a list of the top 500 things we need to do to be in line with our climate targets, what Africa does with its natural gas does not make that list. New long lead time gas projects risk failing to recover their upfront costs if the world is successful in bringing down gas demand in line with reaching net zero emissions by mid‐century.”

At the other end are energy poor, less developed nations, many of which are in Africa. With most hydrocarbon resource-rich Africa just beginning to exploit its natural resources, and very far behind in global development goals, many feel that it is only fair that Africa is allowed to leverage its gas for economic development. For instance, it would provide electricity, without which schools, homes and factories cannot do what is needed to roll back poverty. Goal 7 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals is: “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.”

Currently, Africa lags all other regions on this universally charted goal despite having over 625 trillion cubic feet (tcf), or nearly 15 percent of the world’s natural gas reserves. It therefore argues that, since gas is less of a polluter, it could play the role of a transition fuel, a midway between carbon-heavy fuels like coal and crude oil on one hand and on the most desirable end of the green spectrum, renewables. The point is made that, yes, the environment may be at risk, but in Africa, people are at more risk of basic survival.

The International Energy Agency estimates that despite the abundance of natural gas on the continent, more than 600 million, or about half of the people in Africa, do not have access to electricity, a utility that people in the developed world take for granted. This is a disproportionate 72 percent of such energy poor people in the world.

To understand what this means at country level, take Nigeria for example. Here’s what the World Bank recently reported: “85 million Nigerians don’t have access to grid electricity. This represents 43% percent of the country’s population and makes Nigeria the country with the largest energy access deficit in the world. The lack of reliable power is a significant constraint for citizens and businesses, resulting in annual economic losses estimated at $26.2 billion (₦10.1 trillion) which is equivalent to about 2 percent of GDP. According to the 2020 World Bank Doing Business report, Nigeria ranks 171 out of 190 countries in getting electricity and electricity access is seen as one of the major constraints for the private sector.”

Regarding the debate about Africa’s energy paradox, the transition versus development challenge, we’ve been this way before. Remember the debate about whether the world should embrace computers, for fear that devices could replace humans and a global loss of jobs and livelihoods would follow if computers became ubiquitous and robots took over offices and shop floors. More recently, we all remember the battle about globalisation, whether nations ought to allow their corporate citizens to relocate production activities – read jobs – to countries where labour is cheaper, then repatriate the finished goods to the home market where the purchasing power is stronger. Time has answered these debates, and the answer is the same: economy trumps politics when the chips are down.

It’s no different on the energy front. In an age when transition economics has gained momentum and is accelerating towards greener energy, Africa can only succeed in leveraging its immense gas resources, through pragmatic engagement of the rest of the world, not through sentimentalism. This is especially so because gas peculiarly requires a large outlay of capital to develop, produce, transport, and deliver, and must be traded across all over the world with buyers who must enter long term commercial commitments. Even for domestic applications such as power generation a certain quantum of funded demand and capital investment in infrastructure is required to make gas to power projects viable.

How then must Africa begin the effort to successfully position gas a transition fuel and development driver? Africa must first recognize that energy is a strategic resource not a transactional commodity nor a pure political tool, then go from there.

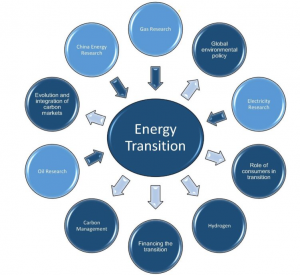

How so? Africa must, one, build a compelling continental consensus about gas as a transition tool, which implies a recognition that transition is an imperative. Two, the continent must develop workable frameworks to translate such a consensus into a commercial engagement with itself and the global energy system (suppliers and buyers). Three, Africa must collectively develop a viable model for accommodating the role of other energy types including the smaller spectrum of the extractive hydrocarbons and non-hydrocarbon derivative fuels such as nuclear and hydrogen, all the way to biofuels and renewables such as solar.

Let’s step back a bit. In the early industrial era, when raw human labour drove industrialization, Africa not only lost out, but it also collectively suffered the deprivation of supplying slave labour to many other parts of the world as they industrialised, without any corresponding value gain. This is not a political reality but a fact of economic history. In the post-industrial era, when raw materials needed to feed the machines became more strategically important than human labour, Africa became the poorly positioned source of all manner of raw materials from diamond to oil and now rare metals to feed the digital electro-machines. Again, this is an economic fact of history, and the outcome of disproportionate positioning. Now, in the age of energy transition, Africa would be missing the target if it relies merely on moaning, sloganeering or summit activism.

The sort of consensus building and hard-grinding work that produced the Africa Free Trade Agreement, rather than complaining ad nauseum at UN meetings, needs to take over.

Africa needs to develop a single viable, sellable framework for positioning gas as a viable transition fuel, within a broader continental framework that syncs with both the transition momentum and the wider energy spectrum, one that sits within the balance between development and transition, in a digital-driven world. Concepts like “just transition” may sound nice and even justifiable, but that’s not how the world works. It is true that Africa has 20 percent of the world’s population, and only three percent contribution to warming emissions, yet bears the brunt of the negative impacts of climate change. But it is also true that the world is moving in the direction of renewables. For instance, around 2002 and 2007, only about 200 gigawatts of renewable power was added globally, but between 2017 and 2022, the figure jumped to 1800 gigawatts.

Africa and its energy policy makers will only start to engage the world when they start to speak in the language that matters: the language of economic realities. To begin with, it needs to start connecting the continent’s resource exploitation objectives with global priorities such as reducing carbon emissions, recognising the full spectrum of resource options, impacts and investment needs, markets and sources of both capital and technology.

We need more of the kind of language in the quote below from Nigeria’s former vice president, Yemi Osinbajo: “The energy access element of the energy transition must be linked with the emissions reduction aspect of the energy transition. For too long, we have considered these to be parallel tracks. If energy access issues are left unaddressed, we will continue to see growing energy demand being addressed with high polluting and deforesting fuels such as diesel, kerosene, and firewood.” Unfortunately, the current body of engagement between Africa and the rest of the world on energy transition, tends to focus on fantasies and denial, as if clamouring for some sort of “energy reparation.”

Regarding the amount of investment Africa requires to meet global development targets, the International Energy Agency states: “The goal of universal access to modern energy calls for investment of USD 25 billion per year. This is around 1% of global energy investment today, and similar to the cost of building just one large liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal. Stimulating more investment requires international support aided by stronger national institutions on the ground laying out clear access strategies – only around 25 African countries have them today.”

So, it just wouldn’t do to merely clench the fist and declare that Africa can decide its own path to transition and what fuel to use to drive development, especially since Africa contributed little to global warming in the first place, compared to the industrialised world that spewed all the carbon into the atmosphere. All that may be true. Again, it is also true that Africa today, in the post-Covid economic reality, is in no position to muster the capital to develop its gas resources nor the purchasing power to pay for its deployment to electricity or anything, without the rest of the world. Africa cannot on its own, either as individual countries or even as a collective, determine and realise its energy future and how it would play in its development trajectory, least of all the role of a complex resource such as natural gas. Africa must engage the energy world, rather than indulge in denial. Otherwise, the continent will miss the transition train.

Happily, there are ways to do this. In fact, the tools for such productive engagement already exist. Let’s highlight just a few of them.

Redefinition of development

Today, there is already a move globally towards a more inclusive definition of development. Sustainable development has replaced plain vanilla development. The World Bank Spring meeting this year is themed “Reshaping Development for a New Era.” So, there is a global acceptance that classic development is not a viable goal anymore; it needs to be made more resilient and sustainable for a world racked with poverty, climate change and digital disruption.

This reopening and redefinition of development presents a fresh window for Africa to engage and table its dilemma of resource wealth and energy poverty, as part of the reframing agenda. Is it possible, for instance, to find accommodation, under certain ring-fences, to extend the time horizon for shutting down hydrocarbon investment beyond 2030 where it is currently pegged in most of Europe and the industrialised West, to allow for transition gas investment? How and where would a 5- or 10-year extension be offset, in terms of targeted investment in gas rich nations to in exchange for supply into energy starved rich countries? Can a conversation be held around accelerating mass adoption of LPG as domestic gas in exchange for deforestation in sub-Saharan Africa with firewood and other biomass, with all the conflicts it produces? Afterall, the reality is that as Africa continues to lag in clean fuel adoption its rising population is increasing emissions by felling more and more trees for firewood. How can such resource utilisation swaps be quantified and readied for as a case for investment, with what guarantees, and by whom? This is the line that needs to be pursued.

The Russia-Ukraine war

The war in Europe has demonstrated the interdependency of nations regarding such resources as oil, gas and even grains. When the war broke out in early 2022, Europe was alarmed by the prospect of Russia weaponizing its gas supply to Europe, resulting in European leaders heading to Africa and anywhere else it could sniff near-term gas supply. Similarly, Africa panicked, since like much of the world, it relied so much on grains coming from Ukraine. Quick fixes had to be worked out to enable Europe to continue receiving Russian gas through last winter, and for Ukrainian wheat to be evacuated to international markets. In the one year of the war, just three European countries, Germany, France, and Italy, imported over $20 billion worth of Russian gas despite sanctions, price caps and the like.

Elsewhere, India used the opportunity of the low price of Russian gas due to the war to triple its gas import from Russia within the year to about $30 billion, procuring the fuel it needs to power its industrial machine, and to meet the target of providing 50 million homes with LPG access. This is a huge market loss to Nigeria for instance, which relies heavily on India as a buyer since the US purchases dropped off when its shale turned US from a net importer to a net exporter. Conversely, South Africa which like India has adopted a pragmatic engagement with Russia through the War, has failed to negotiate any relief for its domestic power crisis that has hobbled its economy in the last year. Our point is that the War in Europe offers African gas producers the opportunity to negotiate an energy-mix consensus within the continent. It also offers the urgency to gain the world’s attention, especially Europe, to rally the necessary investment to develop its gas as a transition fuel at scale, and not waste that crisis.

Unfortunately, African gas owning nations have not sufficiently leveraged the gas-panic in Europe to negotiate substantial gas development financing in Africa. Nigeria for instance has barely even recognized this opportunity, least of all exploit it. It is a prime role of industry thought leaders such as the Nigeria Gas Association to nudge policy makers towards what is achievable, rather than what is not.

Africa Free Trade Agreement

The unprecedented continental free trade agreement has created the world’s largest trading block, measured by the number of participating countries. The World Bank captures its significance this way: “The pact connects 1.3 billion people across 55 countries with a combined gross domestic product (GDP) valued at US$3.4 trillion. It has the potential to lift 30 million people out of extreme poverty, but achieving its full potential will depend on putting in place significant policy reforms and trade facilitation measures.”

What does AfCFTA have to do with gas as a transition fuel? For one thing, it presents perhaps the most compelling recent example of continent-wide collective action on an economic agenda. If concerted necessity and action can deliver a trade agreement, why not a gas development agreement?

Secondly, the economic and commercial activities it could potentially deliver should be channelled into a demand pool that can underpin significant gas project investment at the scale needed to make such significant investment viable. There is also the possibility of using it to create a continental gas market rather than just the national domestic demand that countries like Nigeria have had very little success in force-feeding on its own economy, with understandable resistance by the private sector. How do you power the transportation and the manufacturing capacity needed to deliver the economic activity that AfCFTA targets (eliminate 90% of tariffs, generate $450 billion in new incomes and lift some 30 million Africans from poverty by 2035)? Gas could come handy.

Thirdly, the trade agreement has captured the world’s attention, a rare convening power that could be exploited to negotiate the scope and mechanics of gas as a transition fuel not just in Africa but wherever that bridge needs to be built.

History of energy transitions

The history of global energy transitions presents both a sobering lesson and a practical reference as to relating economic development to energy supply and demand realities. If well considered, African energy policy makers can find therein the insights they need to build viable constructs to exploit the gas resources as a viable transition fuel.

The first lesson is that energy transitions follow technology as inevitable outcomes. The chart below shows for instance, that as the world moved from horse drawn carts and manual farming powered by slave labour in the 1800’s to coal-fired engines in the 1900’s, traditional biomass gave way to a peak in coal use. And as oil-driven automobiles and gas-fueled power plants became more ubiquitous through the 1990’s and the millennium switch, an unavoidable transition to oil and gas happened. Today biomass occupies about the ratios coal used to command in the 1850’s.

The lesson: energy transition follows technology. Africa needs to recognize this, embrace it, and go from there, rather than attempt to fight it. Fortunately, even electric cars must be manufactured often in gas powered factories for the foreseeable future. Mid-industrial powerhouse economies such as India and China need gas to support their huge populations and the industrial complexes that support it. Africa needs to, not only have a commercial conversation with such markets about its gas, but also copy its pragmatism to support their own relatively large and young populations.

Carbon trading

Carbon trading presents a mature concept, globally accepted, but poorly leveraged by Africa. The idea of offsetting carbon emission with greener investment on a virtual commodity exchange is brilliant. Africa is well positioned for this, but its policy makers are either poorly informed or distracted. Think how much credit sub-Saharan Africa could get by quantifying and commercialising its naturally occurring green forests, a carbon trading commodity rather than fallow waste. Could such credit be channelled into low carbon gas projects as a more palatable alternative to crude oil for instance?

Surely, a conversation can be ignited with heavy emitters like China and India which are under pressure to reduce their carbon contribution to global warming. Similarly, a carbon offset conversation can be initiated by large oil and gas multinationals who are facing pressure from their investors to reduce the high-emission crude oil projects, which the companies are insisting they still need to maintain current revenues.

Viable options need to be proposed for investing in lower carbon gas projects in Africa if such can be quantified in carbon offset value terms, rather than resorting to throttling up gas project taxes that end up financing public sector corruption. The reserves addition bonus in Nigeria became an effective policy that produced the big offshore projects in Nigeria such as Bonga and Erha. Such policies, anchored in reality, should be engineered, on a national and continental scale, targeted not just at fiscal incentives but also at the desire of large investors to gain carbon relief.

US Gas commercialization precedent

As 1980 arrived, the US was importing nearly one trillion cubic feet (tcf) of gas and exporting practically none. By 2021, the country was importing 2.8 tcf and exporting over 6 tcf. Summing up the switch, US Energy Information Administration (EIA) says of the data it tracks: “Total U.S. annual natural gas imports in 2007 reached about 4.61 trillion cubic feet (tcf) (12.62 billion cubic feet per day [bcf/d]) and have generally declined each year since then. In 2021, total annual U.S. natural gas imports were about 2.81 tcf (7.29 Bcf/d).”

What happened, and what’s the lesson for Africa’s gas-led transition? One only needs to look at the timing of the US switching from net gas importer to net exporter. It happened around the time technology unlocked the commercial value of shale gas of which the US had an abundance. The US became awash with shale gas, so much so that it needed not only to push through new laws to allow for gas export, but it also needed to physically reconfigure its import terminals to face the other direction as massive export terminals!

Lesson one is that politics, even transition politics, is overshadowed by economic priorities. The leader of the charge against Africa exploiting its gas long term, is currently exporting more gas than all of Africa! Second, transition can coexist with investment. The US has not abandoned gas as a lower-emission alternative to coal (of which it still uses plenty, some 50 million short tonnes every year, mostly for power generation). Nor has it stopped urging the world to work to lower emissions and to push for alternatives at the same time. Interestingly, the largest gas trading partner of the US is its neighbour, Canada.

In conclusion, Africa has done well to push back a bit on the mandate to join the push for decarbonization, and to draw attention to its developmental needs and resources and seek to position gas as a transition fuel. But that is only the beginning. It will take much more to make that proposition viable, to build a consensus on it within the continent and to coax the world to buy in.

Somewhere in the global mix of frameworks, examples, and precedents, such as those we’ve highlighted, lie the sort of pragmatic progression that Africa needs to seek, and build first internally, then in concert with the rest of the world which needs both energy for sustainable development and to reduce the impact of climate change.