ANTHONY KILA

Generally speaking, thinkers and scholars are driven by and seemingly obsessed with a desire for a higher truth, an understanding of the fuller picture or the discovery of a prescription or explanation that works for all, and is considered superior by most. The highest form of recognition for most scholars tends to be the one that comes from their peers. With such a milieu of aspiration and source of validation, it should hence not be surprising to observe that most scholars and thinkers shy away from appearing partisan and linked to a political or even social world view; the trend is to be untaggable because the quest is for a universal and independent message.

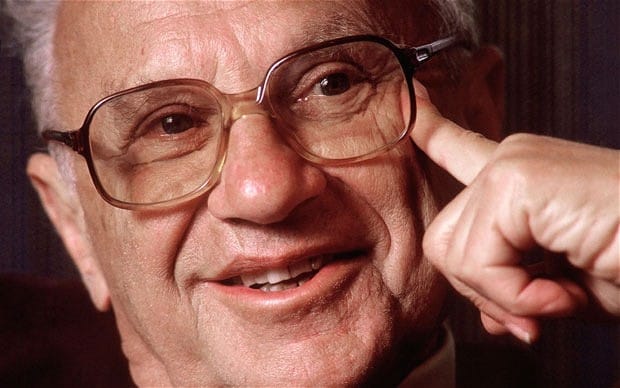

One thinker who had no problem in taking a clear side while constantly and consistently propagating his views and thoughts whilst still able to be held in high esteem by his peers is Milton Friedman, the American born economist, public intellectual, political affairs commentator and Nobel Prize winner. He was born in New York in 1912 and he died in California in 2004. A true self-made man, if one exists, Milton Friedman was the first graduate of his family and he was born with neither title nor money: He was the child of a working-class family of immigrants that came to the USA from Hungary in search of a better life. His father, Saul Friedman died whilst Milton Friedman was in second year of high school, consequently his mother, Rose Ethel Friedman, was responsible for the nurturing of the young Milton Friedman and his two sisters. It was a hard way of growing up, yet our ‘unforgettable’ had good memories of his humble and tough background of which he later recollected as “a family whose income was small and highly uncertain; financial crisis was a constant companion. Yet there was always enough to eat, and the family atmosphere was warm and supportive.”

Many people know and remember Milton Friedman as a champion of the free market and an uncommon antagonist of government intervention or even existence. In reality, Milton Friedman did not want to abolish government; yes, he was wary of government intervention but his idea is to contain government intervention, not to abolish government. You cannot, however, blame those with such extreme views and memories of the man and his thoughts. Milton Friedman is the thinker who once reasoned and announced that, “only [the] government can take perfectly good paper, cover it with perfectly good ink and make the combination worthless.”

Beyond his usually colorful, provocative and witty expressions, one needs to situate his thoughts and ideas in the context of a revisitation and refusal of the theories of John Maynard Keynes, whose method and apparatus were used by Milton Friedman to reject the Keynesian theories, according to Milton Friedman himself. It must be noted here that Milton Friedman was rejecting Keynes at a time when Keynesian theories were not only popular and being applied by governments, but they even seemed commonsensical then: Keynesian positions were largely perceived as the middle way that combined and confined the energies of the market with goodness of government for the benefit of the strong and the protection of the weak. Not for Milton Friedman though, who saw all that as naïve and ultimately inefficient.

Beyond the popularly known case he made for the rejection of government intervention, Milton Friedman’s major contributions include his reexplanation of the consumer patterns, the role of money in the economy and management of inflation and by so doing, became the darling and Maître à penser of politically right leaning politicians, such as the republicans and conservative in the USA and England, respectively. His influence however went beyond Europe and America.

For Milton Friedman, consumption patterns are formed based on future expectations and what he termed as consumption smoothing. With his Permanent Income Hypothesis, he showed us that people tend to smooth out consumption over their lifetime because they want to ensure stability and avoid diminishing marginal utility from decreasing their utility.

Just when just about everyone in government and in academia seemed to have agreed that the fiscal policies of government spending and tax policies were the way to influence the economy, Milton Friedman made his case for the role of money in the economy by leading what is now known as monetarism. For Milton Friedman, instead of the government directly intervening and becoming a player in the system, it was enough and indeed more efficient to manage the supply of money into the system. It is possible to stimulate the economy by controlling the amount of money that enters the system; with that done, the free market, argued Milton Friedman, will adjust itself and all those operating in it will adapt. What determines consumption and production for Milton Friedman is the amount of money in circulation and all that is needed is the control of that quantity by adjusting interest rates which will in turn induce people to save, spend or borrow more depending on the level of the rates. This son of working-class immigrants that grew up doing odd jobs whilst studying refused the idea of government intervening directly for, he felt, government will always make a bad situation worse. He argued that, “when [the] government – in pursuit of good intentions – tries to rearrange the economy, legislate morality, or help special interests, the cost comes in inefficiency, lack of motivation, and loss of freedom. Government should be a referee, not an active player,” he argued.

Off all his purists and contributions, one area in which Milton Friedman tried to consciously make a mark was in corporate governance and he tried doing so by proposing a radical approach, which he himself termed “A Friedman Doctrine” in an essay he published in 1970 where he bluntly argues for the supremacy of private property, shareholders and ownership against any form of collective or societal responsibility or deference to management, articulating that the social responsibility of business is to increase profit. His position generally known as the shareholder theory considers shareholders as the economic engine of the enterprise and that all the business does should be geared towards implementing the desire of shareholders. He argued that, “in a free-enterprise, private-property system, a corporate executive is an employee of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires … the key point is that, in his capacity as a corporate executive, the manager is the agent of the individuals who own the corporation … and his primary responsibility is to them.”

There are few thinkers that combine the status of being one of the most cited, most appreciated and most criticized. Milton Friedman is one of the few.

Join me on twitter @anthonykila to continue these conversations.

Anthony Kila is a Jean Monnet professor of Strategy and Development. He is currently Centre Director at CIAPS; the Centre for International Advanced and Professional Studies, Lagos, Nigeria. He is a regular commentator on the BBC and he works with various organisations on International Development projects across Europe, Africa and the USA. He tweets @anthonykila, and can be reached at anthonykila@ciaps.org

business a.m. commits to publishing a diversity of views, opinions and comments. It, therefore, welcomes your reaction to this and any of our articles via email: comment@businessamlive.com