Onome Amuge

THE AGRICULTURAL SECTOR OF ANY economy basically centres around performing the basic role of food production and sustenance, to feed the population and provision of raw materials for industries to convert into finished products.

The critical role of food in the sustenance of human life is indispensable, thus conferring on agriculture one of the most important sectors of any economy. In this connection, the dawn of Nigeria’s independence on October 1, 1960 came with the expectation that its local agriculture production would perform incredibly well in the provision of food for the “new nation’.

Sixty years have since gone and the country’s agriculture sector has gone through various phases of agricultural policies and development. Business A.M. examines the major agricultural policies and projects established by Nigerian governments, through the Diamond Years, their significant achievements and shortfalls, and how they can be better implemented for sustainability.

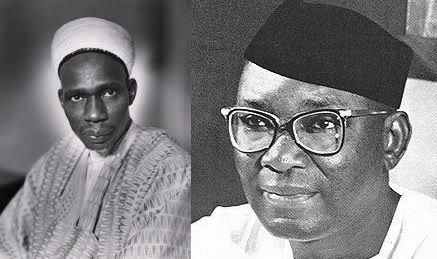

1960-1966: Nnamdi Azikiwe/Tafawa Balewa era

This period, also recognised as the First Republic, marked the first indigenous control of the Nigerian government. According to Yusuf Elijah, an agricultural historian, the development of agriculture during this era was then a primary responsibility of the regions actualised by the Regional Agricultural Programmes (RAPs).

The Regional Ministries of Agriculture were established in 1962 and the major federal responsibility was agricultural research headed by the Federal Ministry of Economics Development. Projections by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) indicated that food production within this period surpassed population growth. The Western region became a predominant producer of cocoa and coffee, the Midwestern region produced rubber, the Eastern region, oil palm and the Northern region was the key producer of groundnut and coffee.

Being an offspring of colonial agriculture, successes were achieved majorly in cash crop production and export earnings. The major setback of this implementation of policy as stated by Yusuf, is that cash crops were given much priority while food crops didn’t receive enough attention. Lack of unity, ethnicity, political disagreements in the regions also thwarted the success of the programme.

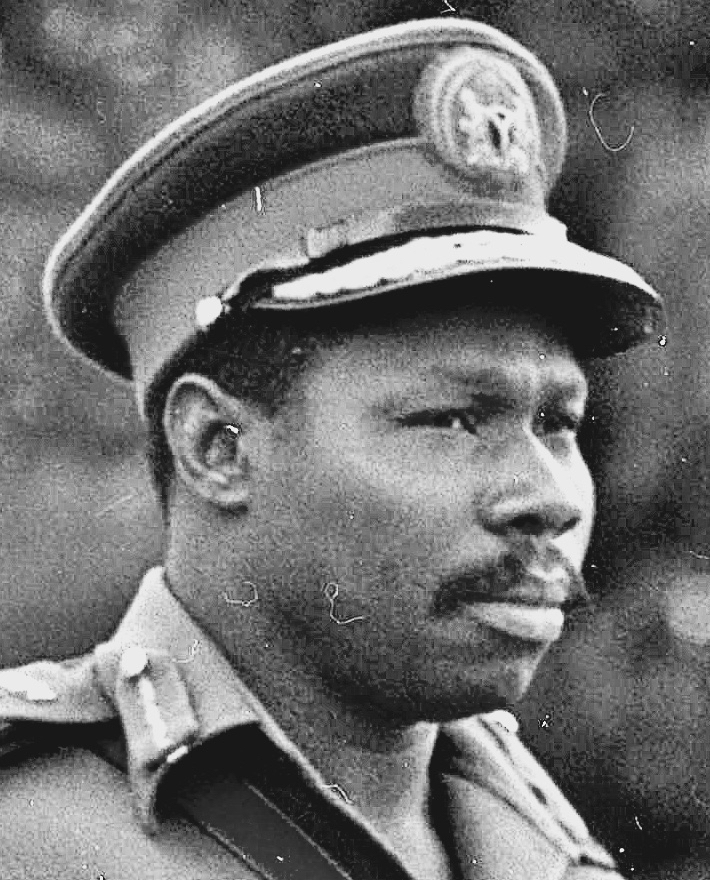

1966-1975: Yakubu Gowon regime

The 1966 military coup brought an end to the First Republic. The civil war also occurred during this period.. Reports by economic analysts show that by 1968, the financial resources of the federal government were under immense pressure as the government focused on military expenditure at the detriment of agriculture and other sectors.

Public debt servicing rose by 57 percent above the 1965 level. The agricultural data recorded that during the 1966-1975 period, agriculture received a meagre 2.2 percent of total federal expenditure. The oil revenue, which had started growing during the civil war era, recorded a boom in the early 1970s.

However, some agricultural programmes were initiated during this period albeit on an inferior scale compared to the race for the dividends of the ‘black gold’. A notable agricultural programme, initiated during this period. is the National Accelerated Food Production Project (NAFPP) established in 1973.

The policy was targeted at increasing food productivity and ensuring food security. Moreso, the first set of the Agricultural Development Projects (ADPs) were initiated in Funtua, Gusau and Gombe. The Chad Basin project and the Sokoto-Rima Valley Authorities were other significant agriculture-based programmes during this period.

These programmes however failed to achieve the set goals as the programme, which was also supported by the World Bank, prioritised commercial agriculture. James Ayatse, an agricultural analyst/academician noted that challenges such as shortage of funds, untimeliness of subsidised input supply, high frequency of labour mobility, dwindling/counterpart funding policies, were some of the challenges that obstructed the success of the agricultural programme.

1976-1979: Olusegun Obasanjo regime

Economic analysts recorded that during this period, the revenue being accumulated from petroleum was on a rise. As a result, food importation escalated while local production plummeted. As the Obasanjo-led administration was now in direct involvement and control of the agriculture sector, several parastatals were established to undertake large scale, mechanised farming.

Notable among the parastatals were the National Grains Production Company, National Root Crops Production Company and the National Livestock Production Company. The River Basin Development Authority (RBDA) and the ADP systems were also revamped.

The Federal Ministry of Agriculture was also created to cement the federal government’s control of the agriculture sector, while the state marketing boards were replaced with National Community Boards. Another initiative and the most popular agriculture programme of the Obasanjo regime was the Operation Feed the Nation (OFN) established in 1976.

The programme saw an aggressive nationwide campaign calling on all Nigerians to delve into agriculture and grow food on any available land. Many Nigerians responded positively, but the campaign was not sustained and yielded little result.

James Ayatse noted that though the programme encouraged domestic food production and self-sufficiency, it failed to achieve its major objectives due to indiscriminate use of land for farming activities, absence of available market, inexperienced hired labour and livestock diseases, which caused havoc on many farms.

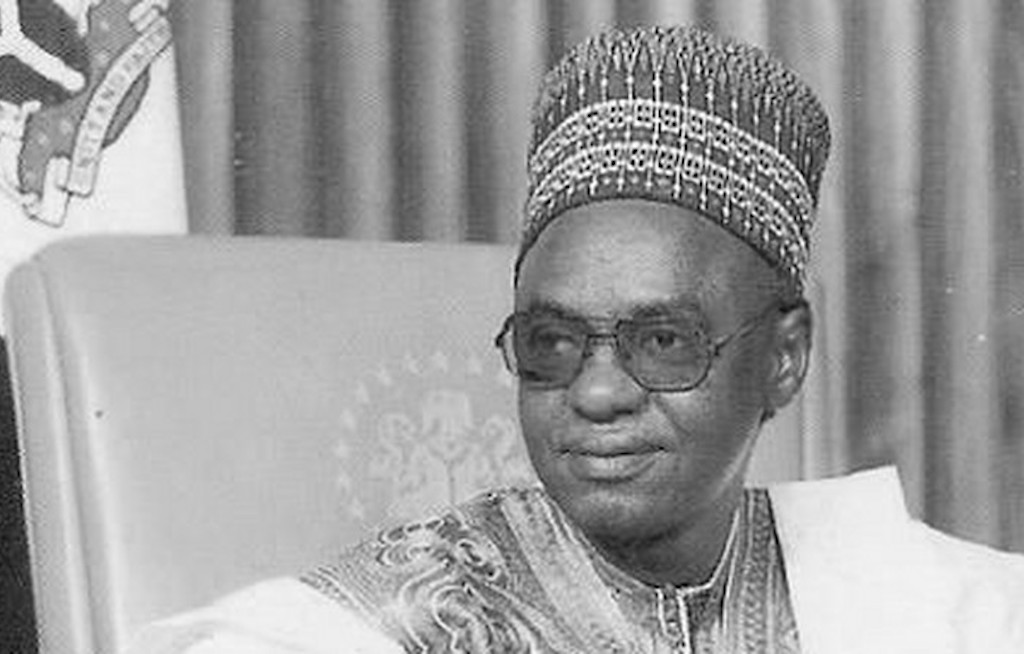

1979-1983: Shehu Shagari Administration

The Shehu Shagari administration ushered in democratic governance after more than a decade of military rule. The agricultural sector, however, continued to suffer as local production kept falling.

According to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Nigeria’s import of maize and rice increased from 9,000metric tonnes in 1970 to 168,000 metric tonnes in 1980, while rice importation escalated from 2,000 metric tonnes to 450,000 metric tonnes within the same period.

Wheat imports rose from 27,000 metric tonnes in 1970 to 1.5 million tonnes in 1982. The country’s foreign exchange earnings also tumbled by 74%, while the debt burden increased by 124%. Nigeria had become heavily an import dependent economy which translated to shortage of major staples, basic essential commodities and consequent food inflation. A tumble in oil production from 2.1 million barrels per day to 640,000 resulted in a drastic fall in revenue.

The Shagari government responded to this by enacting the 1982 Economic Stabilisation Act (ESA). The policy placed severe restrictions on food importation and other agricultural commodities. The ESA also prohibited the exportation of food and other cash crops.

The Green Revolution Programme (GRP) was also launched with emphasis on the expansion of food grains production. The government made efforts at providing a high supply of subsidised fertilizers to farmers and also focused on developing irrigation facilities.

The programme targeted ensuring self-sufficiency in food production and also made attempts at introducing modern methods of mechanised farming. Despite the huge investments the government claimed to have made, the programme was not a success and was halted two years later.

Despite the failure of the GRP of the Shagari regime, economic analysts noted that it raised the relative financial allocation to agriculture beyond the levels provided by previous regimes. The 1981 agricultural allocation was recorded to be 13% of total government expenditure.

1983-1985: Muhammadu Buhari Military administration

The military regime of Muhamadu Buhari facilitated the continuation of the tight monetary and fiscal policies of the ESA. Agricultural commodities, such as rice, wheat, corn, wheat products and vegetable oils, remained banned.

Some of the policy measures specifically directed at the agricultural sector include; the abolition of the commodity boards, increase of budgetary allocation to the Agriculture Development Programme (ADP) systems as a major instrument for agricultural extension and development, completion of One Fertilizer Project and Savanna Sugar Project.

Another agriculture initiative of the Buhari military regime was the Back to Land (BL) Programme established in 1984. The aim of the programme was encouraging massive agricultural production. Dauda Yarama, an agriculture educationist commented that the programme encouraged the engagement of rural farmers in full time agricultural production to close the gap of food insecurity, but it achieved little owing to challenges like insufficient input, technological deficiencies and inadequate data.

1985-1993: Ibrahim Babangida regime

The Babangida administration created the Directorate for Food, Roads and Rural Infrastructure (DFRRI) in January 1986. The programme was designed to improve the quality of life and standard of living of the rural people through agriculture.

The Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) was also adopted in 1986 and it focused on the agricultural sector to achieve its objectives of diversification of exports and adjustment in production and consumption structure of the economy.

The programme provided strategies on food crops, livestock, industrial raw materials, fish production etc. The National Agriculture Land Development Authority (NALDA) was established in 1992 and it was aimed at giving strategic support for land development, promoting better uses of rural land and their utilisation, achieving food sustainability among others.

Francis John, an agricultural analyst noted that these projects achieved some favourable results, they didn’t yield expected results and the major issues of the programme were corruption, misappropriation of funds, lack of accountability and disorganised planning.

1993-1998: Sani Abacha Regime

The First National Fadama Development Project (NFDP-1) was initiated to promote low-cost improved irrigation technology. Though it was established during Ibrahim Babangida’s regime, it was under Abacha’s regime that it was fully implemented.

The World Bank financed programmme was inclined towards increasing the incomes of the fadama users, through expansion of farming activities with high value added output. The 12 states that benefited include: Adamawa, Bauchi, Gombe, Imo, Kaduna, Kebbi, Lagos, Niger, Ogun, Oyo, Taraba and the Federal Capital Territory.

Overall appraisal of the programme by agriculture experts stated that it showed remarkable success as it adopted community driven development with extensive participation of stakeholders at the early stage.

According to Agriscope, an agriculture-based organisation, the challenges attributed to the programme was based on the fact that unskilled handling of water application led to soil degradation in some areas. The Family Support Programme (FSP) and Family Economic Advancement Programme (FEAP) were also agriculture development programmes created by the Abacha administration. They were targeted at encouraging food sustenance especially for the less privileged in the society. These programmes did not achieve much as they were abandoned following the death of Abacha.

1999-2007: Olusegun Obasanjo returned

The National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS) was initiated in 1999 under the civilian administration of Olusegun Obasanjo. One of the objectives of the programme was the actualisation of a 6 percent annual growth in agricultural export and 95 percent self-sufficiency in food.

The farmers engaged in the programme were provided with irrigation, machinery and crop varieties to bolster agriculture productivity. National Special Programme on Food Security (NSPFS) – This programme was launched in January 2002 on a national level and the key objective was food production increment and rural poverty elimination.

Farmers integrated into the programme were educated on farm management and effective utilisation of farm resources, research and extension service training, financial facilitation towards increasing productivity among others. Root and Tuber Expansion Programme (RTEAP) was launched in April, 2003.

It covered 26 states and was designed to address food production challenges. The programme targeted improving root and tubers to about 350,000 farmers in order to boost productivity and income. Taofiq Olanrewaju, a farmer and agriculture analyst, stated that lack of accountability and proper planning were major constraints of these programmes. 2010-2015: Goodluck Jonathan administration

Agricultural Transformation Agenda (ATA):

This programme was initiated by the Goodluck Jonathan led government in 2011 with the motive of solving the constraints affecting the agricultural sector. The specific objectives of the agricultural sector as presented in the ATA blueprint documents include: To secure food and feed for the needs of the nation, enhance generation of national and social wealth through greater exports and import substitution, enhance capacity for value addition by efficiently exploiting and utilising available agricultural resources and enhancing the development and dissemination of appropriate and efficient technologies.

According to Akinwunmi Adesina, the then minister of agriculture, the ATA comprised of four key components which the government used in actualising the ATA project and they included;

Growth Enhancement Support Scheme (GESS) – designed to enhance agricultural productivity through timely, efficient and effective delivery of yield increasing farm inputs

ii. Staple Crops Processing Zones (SCPZs) – An initiative to promote private sector investments for agribusiness development and establish publicprivate partnership for the sustained development of commodity value chains;

iii. Nigeria Incentivebased Risk Sharing for Agricultural Lending (NIRSAL) – Aimed at facilitating and managing agricultural financing by banks to enhance the flow of credit to agricultural sector value chain actors;

iv. Commodity Marketing Corporations (CMCs) – Designed at improving the marketing environment for agricultural commodities and assuring sustainable pricing and market development.

The National Seed Council (NSC) reported an increase in certified seed production by the seed producers from 44,487 Metric tonnes in 2012 to 149,844 Metric tonnes in 2013. Tayo Akingbolagun, President of Catfish Farmers Association (CAFAN) noted that fish farmers were able to get support from the government for the first time in the history of the country.

On the other hand, Adamu Bello, Nigeria’s agriculture minister under the Obasanjo regime described the programme as “uncharitable and misplaced”, adding that the agriculture sector was bereft of development. Economic analysis of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) stated that some of the challenges that marred the programme’s success were unavailability of labour to carry out essential farming activities, high cost of farm input and lack of modern storage facilities.

2015-date: Muhammadu Buhari government Anchor Borrowers Programme (ABP):

This programme was launched by President Buhari in November 2015 with the purpose of creating a linkage between anchor companies involved in food processing and small-holder farmers of the required agricultural commodities.

The ABP, which is supported by the Central Bank of Nigeria, provides farm inputs to small holder farmers to ensure a boost in production. Godwin Emefiele, the CBN governor, while making a speech about the programme in November, 2015 disclosed that a cumulative sum of N55.526 billion was disbursed to over 250,000 farmers who cultivated about 300,000 hectares of farmland for rice, maize, cotton, wheat, cassava and other crops.

Presidential Fertilizer Initiative: This programme was launched in December 2016 following a partnership agreement between the governments of Nigeria and Morocco.

The programme is led by the Nigerian Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) and the Fertilizer Producers and Suppliers Association of Nigeria (FEPSAN). One of the key objectives of the PFI is the actualisation of sustainable and affordable fertilizers for Nigerian farmers.

In six decades of successive governments, Nigeria has waddled through the emergence and eventual desolation of many agricultural policies, a worrisome fact given that agriculture is a key sector of the economy that thrives only on sustenance and consistency.

Halting Programme Discontinuation Armed with this view, Business A.M. spoke with Promise Amahah, an agricultural investor, and National Coordinator of the Nigerian Young Farmers Network (NYFN).

According to him, the major reason for the failure and discontinuation of many of these government-established agricultural programmes is that they lack proper implementation strategy and monitoring to sustain agriculture projects.

He suggested the actualisation of a monitoring evaluation agency to track and monitor all the activities of the government initiatives. Francis Okafor, an agriculture analyst and author of the book, “Integrated Rural Development Planning in Nigeria”, explained that one of the cardinal problems affecting the sustainability of the agricultural policies is inadequate monitoring and inconsistent evaluation of such programmes.

He asserted that evaluation should be thoroughly planned and determined before implementation. Okafor also noted that the abandonment of agricultural development programmes by successive governments deters sustainability. He suggested that the continuity of agricultural development policies should be encouraged and improved by successive governments.

Julie Iwuchukwua, an agriculture educationist at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka blamed the inconsistency in agriculture policies on embezzlement, misappropriation of cash and lack of funds to pursue specific policy or programme to an expected end. She advised that a well-documented and workable plan should be a priority before the government begins to channel funds into the policy projects. She also called for the implementation of systematic technical advisory services to help sustain the projects