Vilfredo Pareto; A mathematical response to problems in economics

May 23, 2022876 views0 comments

BY ANTHONY KILA

One of the major differences between those that studied or applied economics in the 18th and 19th century and those that studied and applied economics from the 20th century onwards is their conception of economics. For the former, economics, known generally as political economy, was a branch of philosophy and other moral reflections aimed at the understanding of wealth creation and suggesting improved ways of governing the society and improving the welfare of citizens. The reflections and language of that era was commonsensical and the messages were generally intuitive and inspirational. For students and economists of our time, economics is mostly a study of gathered data and it is expressed in mathematical laws. The economics of our times is a lot about statistics, tables, graphs and equations.

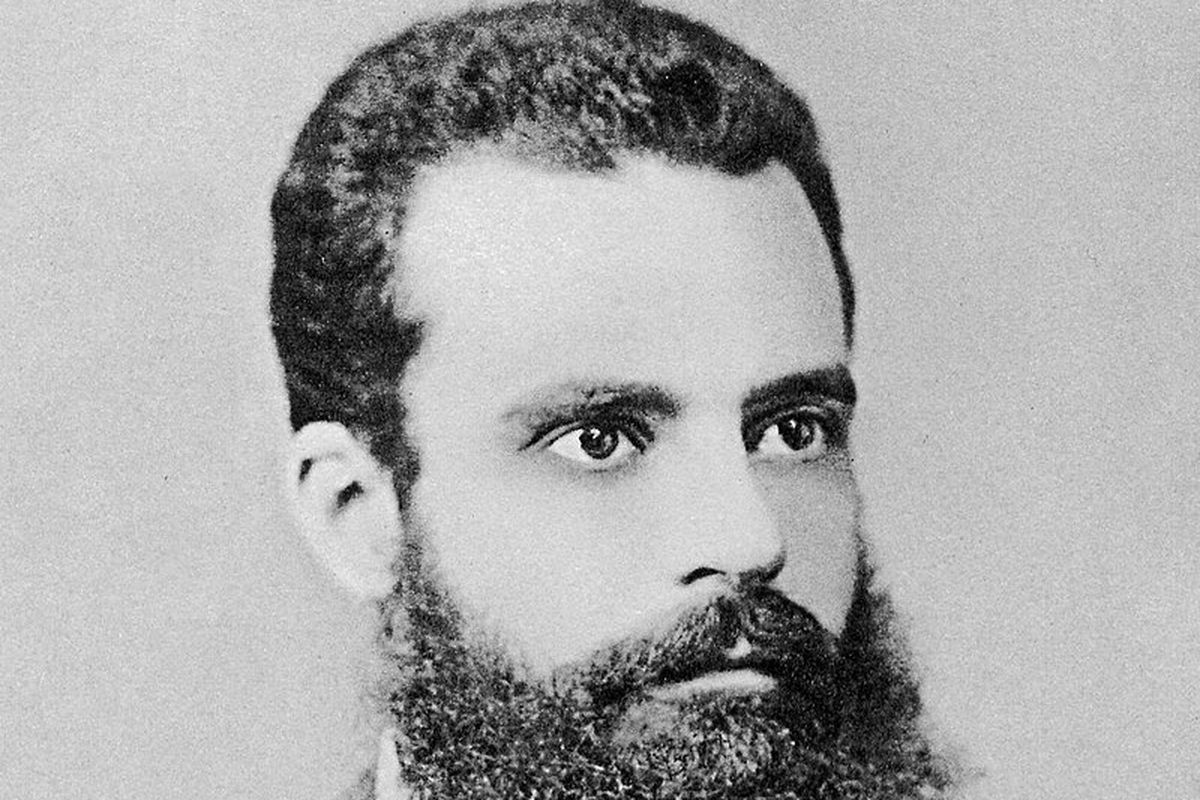

Our unforgettable today is one of those that led the metamorphosis of economics from its original state into a mathematically driven study of human relations. His name is Vilfredo Pareto and he was born in 1848 to an aristocratic family in Paris. His father, Raffaele Pareto, was an Italian engineer and nationalist whilst his mother, Marie Metenier, was a French activist. Vilfredo Pareto lived for 75 years during which he contributed to an array of disciplines. He is remembered generally as an engineer, philosopher, political scientist, sociologist and economist. Interestingly, Vilfredo Pareto came into economics late in life and we owe his entrance into economics largely to Maffeo Pantaleoni.

Vilfredo Pareto’s first over 40 years of studies and profession was around mathematics, engineering and philosophy. He studied mathematics and physics, and got his doctorate in engineering. He started out as an engineer and later became a company director and he tried his hands on partisan politics, but unsuccessfully. So much was his belief in the natural scientific method that even when he approached sociological studies, he insisted on basing sociology on such a method that he once declared: “my wish is to construct a system of sociology on the model of celestial mechanics, physics, and chemistry.”

Vilfredo Pareto’s first major contribution to economics was his articulation of wealth distribution, when in his 1895 publication based on data he collected first in England and later in other countries, he used mathematical formulae (logarithm expressions) to explain that most of the wealth of every society is in the hands of a very few. He also showed that such skewed distribution was neither random nor accidental but followed a clear pattern that indicates that no matter where you go in the world or at any time in history, wealth has always been and will always be distributed in a way that the very few will always possess most of the available wealth and the very many will have lowest portion of available wealth. His articulation of wealth distribution has been named the Pareto Distribution.

So much impact has the Pareto Distribution made in our lives and across so many disciplines that after over 120 years since it was introduced, many now use it and in different ways beyond the original reason of its conception. His observation now held as universally valid by many is presented in different situations and in many shades, sometimes as the “80 20 Rule”, the “Pareto Law”, “Pareto Principle” or the “Vital Few”. The latter expression was coined by Joseph Juran.

Today, many of us discover Vilfredo Pareto in sales and marketing planning sessions when we are shown that 80% of our goods and services are purchased by only 20% of our customers or that 80% of our revenue comes from just 20% of our offers; or in manufacturing and general production planning sessions, where we are shown that 20% of production inputs account for the 80% of our total production. The principle is also very well cited and applied in general business and project management sessions, where it is held that 80% of donated or invested funds and general participation comes from 20% of participants. Readers in and scholars of underdeveloped countries will readily observe that a government capable of solving a few problems such as justice system, security, infrastructure and education would have resolved 80% of the problems facing the development of such a country.

A realist to the core, Vilfredo Pareto also introduced an important element to our understanding of welfare economics: the zero-sum property of economic policies. For Vilfredo Pareto, a system or an economy will be said to be in optimum or efficient state when it is impossible to reallocate resources for the benefit of an individual without this having a cost or disadvantage for another individual. This theory is based on and must be contextualised in the idea that in the economy or system in question, all the resources and goods have been allocated to its maximum efficiency. The economy of a situation that reflects or responds to this theory is described as having a “Pareto Efficiency” or “Pareto Optimality” by those in favour, as well as those against the theory. It has been argued that like the perfect market managed by the invisible hand of classical economists, the Pareto Efficiency at least in its purest form can only be conceived and studied in theory or regarded as a possible outcome.

It is worth noting that whilst Vilfredo Pareto made a lot of impact with his introduction of mathematics into the study of economics and even took over the political economy chair formerly held by Léon Walras, another mathematical economist that greatly influenced him, Vilfredo Pareto spent the later part of his life in sociology where he also made remarkable contributions, and yes, he tried to take his mathematical methods there, but he eventually concluded that men were not as logical as they desire or pretend to be.

Join me if you can @anthonykila to continue these conversations.

Anthony Kila is a Jean Monnet professor of Strategy and Development. He is currently Centre Director at CIAPS; the Centre for International Advanced and Professional Studies, Lagos, Nigeria. He is a regular commentator on the BBC and he works with various organisations on International Development projects across Europe, Africa and the USA. He tweets @anthonykila, and can be reached at anthonykila@ciaps.org

business a.m. commits to publishing a diversity of views, opinions and comments. It, therefore, welcomes your reaction to this and any of our articles via email: comment@businessamlive.com