Much of Jamilatu Mohammed’s harvest of cocoa beans is sitting in a storage shed near her dilapidated mud house along Ghana’s western border when it should be on its way to factories of chocolatiers like Nestle SA.

The mother of two and other small growers in the world’s no. 2 producer represent the casualties in a global price slump triggered by traders in London and Singapore and aggravated by bureaucrats in distant African capitals.

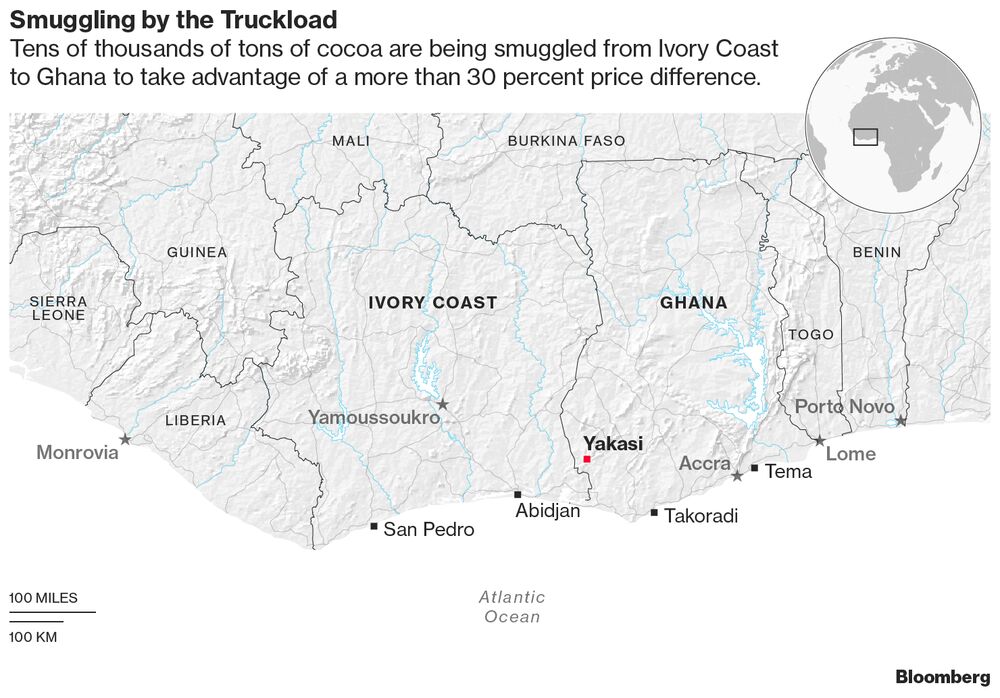

Cheaper beans from neighboring Ivory Coast, the biggest supplier, are flooding the local market and luring the Ghanaian state-licensed agents who were essentially her only customers.

“Things have never been this hard,” Mohammed, 33, said while drying a batch of ripened reddish-orange beans on a makeshift workstation made of bamboo sticks outside the family home, her four-year-old son by her side. “We know the purchasing clerks are going to the border with trucks to buy cheaper cocoa from Ivory Coast.”

The big cocoa harvest starting in October is set to make things worse. The cocoa board barely earns enough to purchase beans at a more than 33 percent premium on Ivory Coast crop and the nation is struggling to narrow its budget deficit even with International Monetary Fund help. That reveals a risk investors who drove Ghana’s junk-rated Eurobonds to record highs this year may be ignoring.

It’s almost impossible to monitor the scale of illicit trading between the countries supplying 60 percent of the world’s cocoa because their borders are porous. Ivory Coast’s cocoa regulator estimates about 70,000 tons of beans were smuggled into Ghana this season, equal to at least 7 percent of Ghana’s annual production. People familiar with the trade forecast that figure will multiply with the next crop.

“Cocoa farmers are supposed to have money, but here we are very poor”

In Yakasi, the village where Mohammed and her husband run a small cocoa tree plantation, dozens of the Ghanaian middle men cross the border by truck or motorbike to haul in beans officially priced at $80 per 64-kilogram bag. They then sell it to the Ghana Cocoa Board whose farmgate price is $107 a bag and pocket the difference, increasing the strain on a body that’s already 10 billion-cedi ($2.25 billion) in debt.

Several agents and farmers, including Mohammed, told Bloomberg in July they hadn’t been paid in months because of the board’s financial troubles. The regulator may have cleared that backlog with funds raised on local bond markets and an annual harvest loan from banks including Societe Generale SA and Deutsche Bank SA.

“Ghana’s already overstretched and anything that exacerbates that weakness is going to be a concern,” said Stuart Culverhouse, the London-based head of sovereign and fixed-income research at Exotix Capital, which recommends holding Ghanaian bonds.

There’s a long history of smuggling between the two countries, yet rarely so prolific. Years of raising the fixed price paid to farmers before the harvest encouraged growers in Ivory Coast to plant new cocoa trees. With many now mature enough to yield crop, there’s little relief to a global surplus Citigroup Inc. predicts will amount to 70,000 tons next season.

To mirror the more than 40 percent collapse in cocoa since 2015, Ivory Coast cut the price of local beans in April. But for Ghana, changing the farmgate price is politically difficult because thousands of poor family farmers were hit as the cedi lost more than half its value since 2013, stoking the cost of imports such as fertilizer.

President Nana Akufo-Addo won elections in December by appealing to voters in the three largest cocoa-producing regions with promises to boost agricultural output and lift prices. That pledge became elusive as global prices slumped about a third in 12 months to under $2,000 a ton. Ghana pays farmers just over $1,700 a ton, leaving little room to manoeuvre.

“I just don’t think it’s sustainable,” said Edward George, the London-based head of research at Ecobank Transnational Inc., another of Ghana’s lenders. “If they keep the price high, all of this new production that’s come on is going to encourage farmers to take every pod they can.”

African countries vow to fight illegal timber trade to boost GDP

Nigeria cocoa output seen rebounding in 2017/18

Ghana Cocoa Board Chief Executive Officer Joseph Boahen Aidoo isn’t planning to cut prices and says there’s “no proof” of smuggling. “We can’t expose our farmers to the volatilities and vagaries of the world market price,” he said in an interview.

Near the border, though, several growers balancing 44-pound bags of beans on their heads tell a different story. Unlike peers in Ivory Coast who trade with international clients via auctions organized by the state, these growers are legally bound to sell only to the very licensed agents who cheat the system.

One grower, 52-year-old mother of five Fatima Alhassan, was forced to take her load back to her village, Aduaku, five miles from Yakasi because none of the agents she approached had cash.

Yet the following morning, a truck lugging six tons of beans rumbled past the local customs point, presumably headed to one of the two Atlantic Ocean ports where cocoa is stored before shipment. The driver said he’d come from Dibi, an Ivory Coast village about 18 miles down a narrow, rocky road meandering through a stretch of forest.

A customs officer stationed at the crossing blocked by a low-hanging wooden gate said smugglers often drive through at night, when it’s too dangerous for him to go outside to question them because of all the poisonous snakes in the area.

Riding out the next harvest will be tough for Ghana, especially with expectations its cocoa board will need to dip into an emergency national stabilization fund or other loans to support farmers. “The government may eventually have to step in to bail them out,” said Edem Harrison, a research analyst at Frontline Capital Advisors in Accra.

Ghana and Ivory Coast agreed in May to pursue a joint cocoa strategy, including possibly building storage facilities to keep surplus beans and release stock based on market demand, functioning more like a cartel.

For border-side growers like Mohammed, there’s no immediate relief. If she doesn’t make money next season, she may leave cocoa farming to her husband and find a menial job to save up her boys’ school fees.

“Cocoa farmers are supposed to have money, but here we are very poor,” she said. “This government promised us it would raise cocoa prices, but now we aren’t even getting paid.”

Courtesy Bloomberg