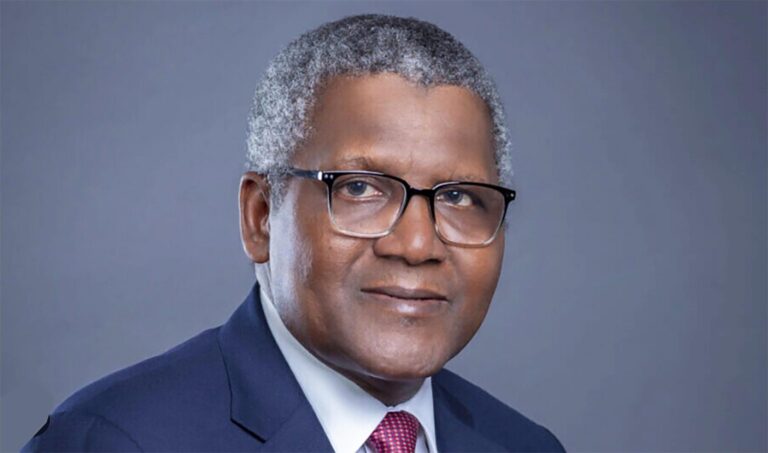

Africa is increasingly becoming a recipient of cheap, often toxic, and substandard petroleum products, a concerning trend driven by the continent’s deficit in domestic refining capacity. Aliko Dangote, president and chief executive of Dangote Industries Limited, made the assertion during the West African Refined Fuel Conference in Abuja, co-organised by the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA) and S&P Global Commodity Insights.

Dangote noted that despite producing seven million barrels of crude oil per day, Africa imports over 120 million tonnes of refined petroleum products annually, incurring an estimated cost of $90 billion. This contrasts with the continent’s domestic refining output, which covers only about 40 per cent of its 4.3 million barrels per day consumption. In comparison, industrialised regions like Europe and Asia refine more than 95 per cent of their consumed petroleum products.

“While we produce plenty of crude, we still import over 120 million tonnes of refined petroleum products each year, effectively exporting jobs and importing poverty into our continent,” Dangote asserted. He framed the $90 billion import bill as a massive market opportunity being captured by regions with surplus refining capacity, noting that only about 15 per cent of African countries have a GDP greater than $90 billion. “We are effectively handing over an entire continent’s economic potential to others—year after year,” Dangote lamented. This fiscal drain and economic leakage, he argued, undermines Africa’s developmental aspirations and perpetuates a cycle of dependence.

While affirming his belief in free markets and international cooperation, Dangote stressed that trade must be anchored in economic efficiency and comparative advantage, not at the expense of quality or safety standards. He criticised the illogical practice of Africa exporting raw crude only to re-import refined products, which the continent is “more than capable of producing ourselves, closer to both source and consumption.” This sentiment underscores a strategic imperative for African nations to invest in and support local refining capabilities to achieve energy self-sufficiency and foster value addition.

Reflecting on the monumental undertaking of delivering the Dangote Petroleum Refinery, the world’s largest single-train refinery, Dangote detailed a litany of technical, commercial, and contextual hurdles unique to the African operating environment. He described the facility as one of the most capital-intensive and logistically complex industrial projects ever constructed.

The sheer scale of the endeavour involved clearing 2,735 hectares of land—seven times the size of Lagos’s Victoria Island, 70 per cent of which was swampy, necessitating the pumping of 65 million cubic metres of sand for site stabilisation and elevation. The project also required over 250,000 foundation piles and millions of metres of piping, cabling, and electrical wiring.

The human capital mobilisation was equally immense, with over 67,000 people on-site at peak, including 50,000 Nigerians, coordinating across hundreds of disciplines and nationalities around the clock. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic introduced further complexities, disruptions, and risks, setting the project back by two years.

Beyond the core refinery, the project necessitated the construction of a dedicated seaport, as existing Nigerian ports were inadequate for the size and volume of equipment required. This included handling over 2,500 pieces of heavy equipment and 330 cranes, alongside the establishment of the world’s largest granite quarry with a production capacity of 10 million tonnes per year. “In short, we didn’t just build a refinery—we built an entire industrial ecosystem from scratch,” Dangote remarked, highlighting the integrated nature of the investment.

Despite the technical triumph, the refinery has encountered commercial challenges. The drastic depreciation of the Naira, from N156 per dollar at the project’s inception to N1,600 per dollar at its completion, has inflated costs considerably. More critically, the refinery has struggled to secure crude oil at competitive terms.

“Rather than buying crude oil directly from Nigerian producers at competitive terms, we found ourselves having to negotiate with international trading companies, who were buying Nigerian crude and reselling it to us—with hefty premiums, of course,” Dangote revealed. He added, “As we speak today, we buy 9 – 10 million barrels of crude monthly from the US and other countries,” though he did commend the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPC) for providing some domestic crude cargoes.

Logistical and regulatory bottlenecks have further compounded the challenges. Port and regulatory charges reportedly account for a staggering 40 per cent of total freight costs, sometimes amounting to two-thirds of the vessel chartering expense itself. Dangote contrasted this with India, where refiners purchasing crude from even more distant regions enjoy lower freight costs due to the absence of such exorbitant port charges.

A major impediment to regional trade and local refining profitability is the lack of harmonised fuel standards across African nations. “The fuel we produce for Nigeria cannot be sold in Cameroon or Ghana or Togo, even though we all drive the same vehicles,” Dangote lamented. He argued that this fragmentation benefits only international traders who thrive on arbitrage, imposing unnecessary inefficiencies on local refiners. As an example, he cited Nigeria’s diesel cloud point standard of 4 degrees Celsius, which limits crude processing options and adds cost, despite few places in Nigeria experiencing such low temperatures, while other African countries maintain a more reasonable range of 7 to 12 degrees.

Adding to these woes, Dangote pointed out the growing influx of discounted, low-quality fuel originating from Russia, often blended under price caps and dumped in African markets. He warned that some of these products are “blended to substandard levels that would never be allowed in Europe or North America,” posing environmental and health risks.

In a call to action, Dangote urged African governments to emulate the protective measures implemented by the United States, Canada, and the European Union for their domestic refiners.