Onome Amuge

Africa’s remittance inflows could reach $168.2 billion by 2043 if robust reforms are implemented, compared with a baseline trajectory of $137.2 billion, according to a new report from the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), a Pretoria-based think-tank.

The report showed that remittance flows into Africa climbed to a record $95 billion in 2024, consolidating their place as one of the continent’s most reliable sources of external finance,

The study showcased how remittances have not only caught up with foreign direct investment (FDI) and official development assistance (ODA) in scale but in some years have overtaken them.

Over the past decade, remittances rose from about $53 billion in 2010 to $95 billion last year. Their share of Africa’s gross domestic product expanded from 3.6 per cent to 5.1 per cent during the same period. The ISS described the flows as one of Africa’s largest and most stable sources of external finance.

Egypt, Nigeria and Morocco remained the continent’s top three recipients of remittances in 2024, reflecting the size of their diasporas and reliance on overseas transfers to fund household consumption. Nigeria, which has historically ranked first, trailed Egypt last year as Cairo benefited from inflows linked to its large expatriate workforce in the Gulf and Europe.

On the flipside, Angola, Seychelles and São Tomé and Príncipe each received less than one per cent of total inflows, underscoring wide disparities across the continent. Regionally, North Africa and West Africa attracted the largest volumes.

In comparison, FDI inflows to Africa stood at $97 billion in 2024, just above remittances. But nearly 36 per cent of that foreign investment was concentrated in a single urban development project in Egypt, leaving about $62 billion spread across the rest of the continent. “This demonstrates that remittances, unlike FDI, are more broadly distributed and directly impactful at the household level,” the ISS noted.

Unlike ODA or FDI, which are mediated through governments or corporations, remittances typically reach households directly, allowing families to fund food, healthcare, housing and education. In countries where formal employment opportunities are limited, remittances play a vital role in sustaining livelihoods.

The ISS report cited Kenya and Gambia as examples, noting that in 2019, about 65 per cent of Kenya’s population and nearly half of Gambia’s population relied on remittances as a key source of income. In fragile states such as Liberia, South Sudan and Somalia, remittances account for more than 10 per cent of GDP.

“Recipients spend most of these funds locally, stimulating trade and services, and in some cases investing in community infrastructure. They are therefore pivotal not only in reducing poverty but also in supporting small-scale economic activity,” the report said.

Despite their growing scale, much of Africa’s remittance flow is seen to be channelled through informal means such as hand-carried cash or unregistered money transfer operators. This is especially prevalent in countries like DR Congo, Libya, Somalia, Zimbabwe and Nigeria, where weak financial infrastructure or restrictive regulations encourage households to bypass formal banking systems.

This reliance on informal networks undermines financial inclusion, obscures the full scale of diaspora contributions and complicates policy planning. “Closing the gap between remittances’ potential and their current use requires action on three fronts: lowering costs and formalising flows, integrating them into national financial systems and creating incentives for diaspora investment,” the ISS argued.

The average cost of sending money to Africa was about five per cent of the amount transferred in 2023, significantly higher than the UN Sustainable Development Goal target of three per cent by 2030.

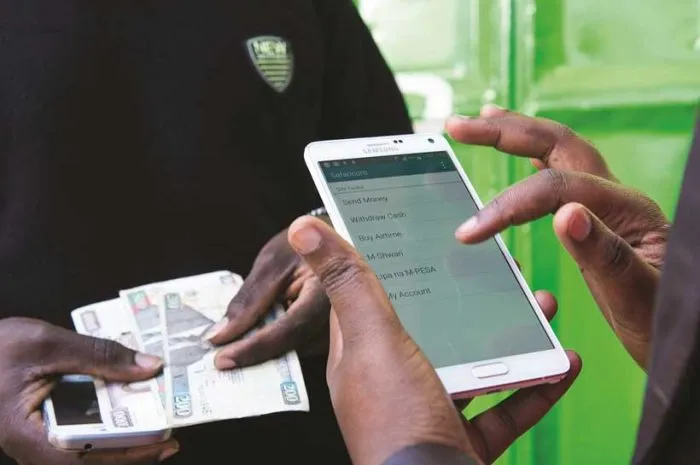

The rise of fintech and mobile money services is starting to lower these barriers. This is as platforms such as M-Pesa, MTN MoMo and Airtel Money have transformed the ease of cross-border transfers, while blockchain-based and peer-to-peer applications promise further cost reductions.

Continental initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Area’s digital trade protocol and the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) also aim to harmonise rules and reduce transaction costs, enabling formal remittance corridors to scale.

However, progress is uneven. The report noted that few African countries have developed robust frameworks to link remittance inflows with savings, insurance or productive investment products. “As a result, their potential as an overarching development lever remains largely untapped,” it said.

Turning remittances into a more structured source of development finance is seen as a critical next step. Some governments are exploring diaspora bonds, targeted savings schemes and tax incentives to channel inflows into infrastructure and enterprise. But overreliance carries risks, including vulnerability to economic shocks in host countries and exposure to cybersecurity threats as digital transfers expand.

The ISS noted that while the bulk of Africa’s remittance inflows originate from the Gulf, Europe and North America, intra-African transfers are growing. Around $20bn of remittances in 2023 stemmed from migration within Africa itself, pointing to the importance of regional labour mobility.