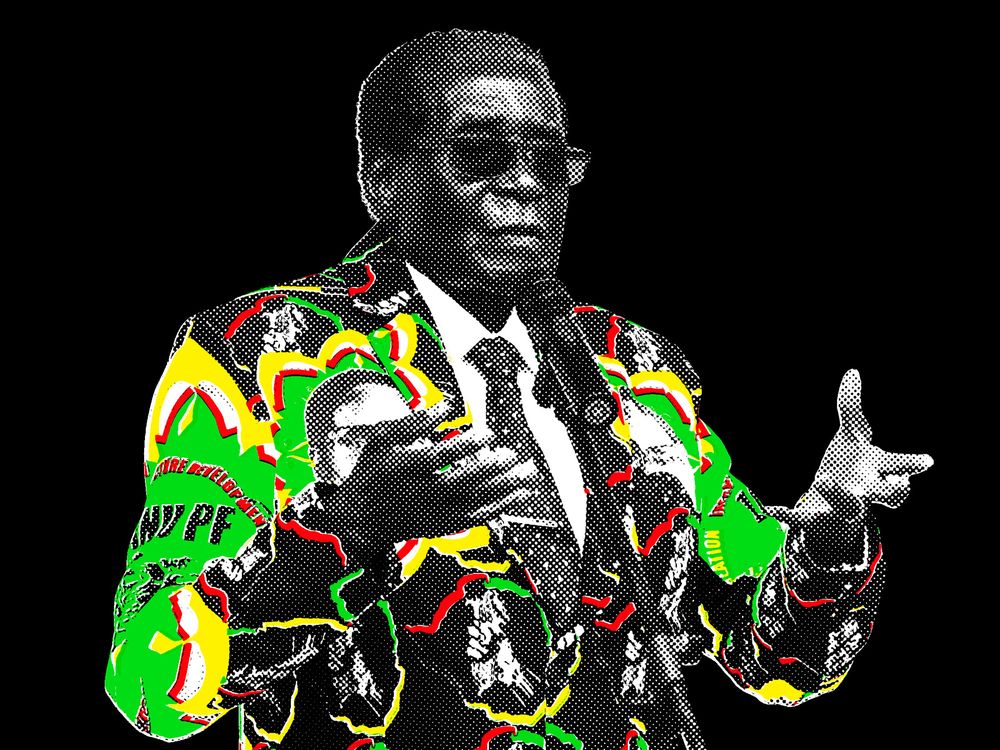

As a rebel, revolutionary, Machiavellian manipulator, and supreme leader, Robert Mugabe has been the face of Zimbabwe for so long that it’s almost impossible to imagine the country without him. Almost. The impossible finally began to happen on Nov. 14, when tanks rolled into the capital, Harare, and the armed forces took custody of Mugabe and his wife, Grace. Military spokesmen said they were “safe and sound and their security was guaranteed.”

Mugabe has ruled for 37 years—the entire existence of Zimbabwe after the downfall of the white minority government of what was then called Rhodesia. In that four-decade period, the economy has deteriorated from resource-rich breadbasket to basket case. Violent repression made Zimbabwe’s leader a pariah to most of the world. Mugabe’s visage became a face loved only by fellow leftist autocrats and the commodity-hungry Chinese government. Indeed, Chinese trade to the southern African nation last year was worth $1.6 billion; Zimbabwe’s military maintains close ties with Beijing’s generals.

More important, despite economic decline and international isolation, Mugabe was the undisputed master of Zimbabwe, outmaneuvering several would-be successors, including the co-leader of the uprising against white rule, Joshua Nkomo. His regime appeared to be getting ready for its third vice president in three years when the military took possession of the streets and the government television station. Mugabe, 93, had been expected to anoint Grace, 52, as the new vice president.

The fall of Mugabe hasn’t led to dancing in the streets. It’s nothing like the developments in the late 20th century that resulted in the collapse of the Soviet bloc or the overthrow of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, where people power stirred the promise of democratic revival and reform. The military action, which the generals refused to call a coup d’état, is the latest chapter of a bitter fight within Mugabe’s political regime, one that’s resulted in the president being caught in his own web of intrigue and betrayal. The leader of this uprising, general Constantine Chiwenga, commander of the armed forces, is a close ally of Grace’s fiercest rival, the deposed heir apparent, Emmerson Mnangagwa. A comrade-in-arms of the president during the fight against the white regime, Mnangagwa also used to run the country’s fearsome security apparatus. His nickname is “The Crocodile.”

As the military took over the state broadcaster, a spokesman insisted Mugabe wasn’t a target. “We are only targeting criminals around him who are committing crimes that are causing social and economic suffering in the country in order to bring them to justice,” Major General Sibusiso Moyo said. It remains to be seen if one of those enemies of the people will be Grace. A polarizing force, the first lady has never been shy about her ambitions or her enmity with Mnangagwa. In recent years, she’s become the center of the youth faction of Mugabe’s ruling party. To her husband’s annoyance, Mnangagwa’s allies repeatedly used this line against her: “Leadership is not sexually transmitted.” On Nov. 6, the president fired Mnangagwa, who fled the country saying he feared for his life. On Nov. 13, Chiwenga, who’d just returned from a trip to China, declared, “When it comes to matters of protecting our revolution, the military will not hesitate to step in.” The next day, it did.

Mugabe’s rule hasn’t made it easy for a democracy to sprout—even though the country has democratic institutions and a viable if outmaneuvered, an opposition party. Autocrats don’t inculcate democracy in their realms. Pressured into elections in the past, Mugabe has managed to subvert the results and remain in power, proving that democracy isn’t a fruitful path for anyone with real political ambitions in Zimbabwe. The military intervention does nothing to change that. The country writes Bloomberg View columnist Eli Lake, “deserves better. It’s not too late for the military to prepare for a real transition to democracy and call for elections. But it’s almost certain the generals will not. For now, it appears they have paved the way for the dictator to be replaced by one of his henchmen.”

To understand the dynamics of the events in Harare, a comparison is best made to what happened in Egypt in 2011, according to Tony Karon, an anti-apartheid activist in South Africa who’s now an editor at Al Jazeera. While most people saw a popular uprising overthrew President Hosni Mubarak, the Egyptian military used the so-called Arab Spring to make sure Mubarak, whom they supported, didn’t get the opportunity to anoint his son Gamal as his successor—even if they had to detour their plans through a brief period of Muslim Brotherhood rule. Zimbabwe’s military, which has officers who’ve trained in Egypt as well as China, has apparently managed to outmaneuver Mugabe’s installation of his wife as his heir.

Why not oust the president completely? That may yet occur. But Robert Mugabe is still the historic face of the revolution—and a face-saving transition may need to take place. The comparison this time is to China, where Jiang Qing and the rest of the Gang of Four were poised to take power after the death of Jiang’s husband, Mao Zedong, the founder of the communist People’s Republic of China. After they were foiled and arrested, Hua Guofeng, a transition figure, was billed by government propagandists as Mao’s true ideological heir to explain why his very visible widow was now completely out of the picture. Deng Xiaoping, the real mastermind of Jiang’s overthrow, eventually took over the actual reins of power.

In Zimbabwe, those reins are in the hands of Chiwenga and Mnangagwa. If the past is the precedent, their ascent doesn’t promise institutional change. Mnangagwa has been tied to—though he’s denied being part of—a bloody purge in the 1980s of the Ndebele ethnic group in the southern part of the country. The genocide, perpetrated by a brigade trained by North Koreans, may have killed as many as 20,000 people. So terrifying were the forces unleashed that hardened operatives of South Africa’s intelligence services were said to fear to fall into the hands of Zimbabwe’s security forces. When I was news director of another magazine, one of our correspondents went to Zimbabwe and was picked up by the police in a small town in the south for practicing journalism without permission. Only in the nick of time were we able to organize his escape before officials from Harare arrived to take over his questioning.

Mugabe is now at the mercy of his military protectors. He may yet manage to overcome them. He’s emerged from other seeming defeats before. But the president has health problems and is in his dotage. This may be the end of his long run. The fall of tyrants is always the stuff of morality plays—and Mugabe will provide history with variations on the ancient verities of absolute power. The more immediate question is: Will the new masters of Zimbabwe change the country?

Again, according to Karon, the comparison is to Egypt. After overthrowing the Muslim Brotherhood, General Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi eventually assumed the presidency and, outlasting international criticism, became the acceptable face of the country, one that was more amenable to international investors as the military that supports him promised stability. Zimbabwe may try the same with Mnangagwa or another figure.

That’s both a danger and an opportunity. It’s a danger because a broader international embrace of Zimbabwe’s leadership will bolster the military and security forces’ control of the country. It’s an opportunity because the global community can try to leverage its financial influence to force structural political reforms. For Zimbabwe, it may not matter—as long as the Chinese love the new face of the nation, whoever that will be.

Courtesy Bloomberg