- About $200 billion of emerging-markets debt owed to China has gone unreported in official statistics in recent years

By WSJ

A hidden pile of debt threatens dozens of emerging-market countries as the global economy stalls and commodity prices tumble.

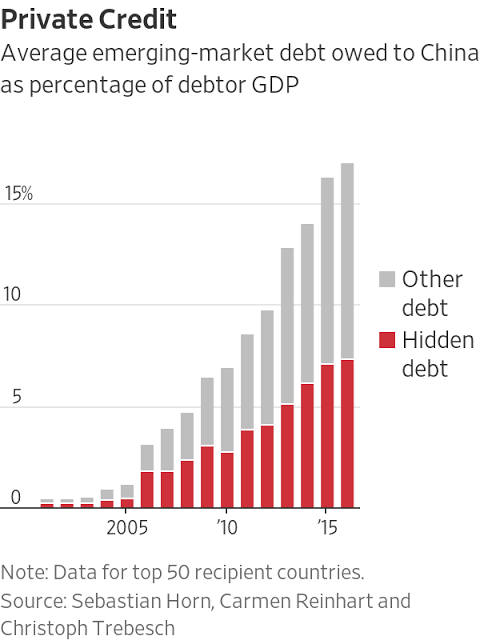

An estimated $200 billion of emerging-market debt owed to China has gone unreported in official statistics in recent years. The money is upending assumptions made by yield-hungry investors who have poured roughly $2 trillion into risky emerging markets over the last decade.

Even before the market crash, some borrowers were buckling under their debts to China. Pakistan turned to the International Monetary Fund in 2018 for a bailout. Sri Lanka was forced to cede China control of a strategically located port to shore up state finances.

U.S. and European economists are drawing parallels to the 1980s debt crisis that shattered growth in Latin America. A global recession would magnify the problem, economists and investors say.

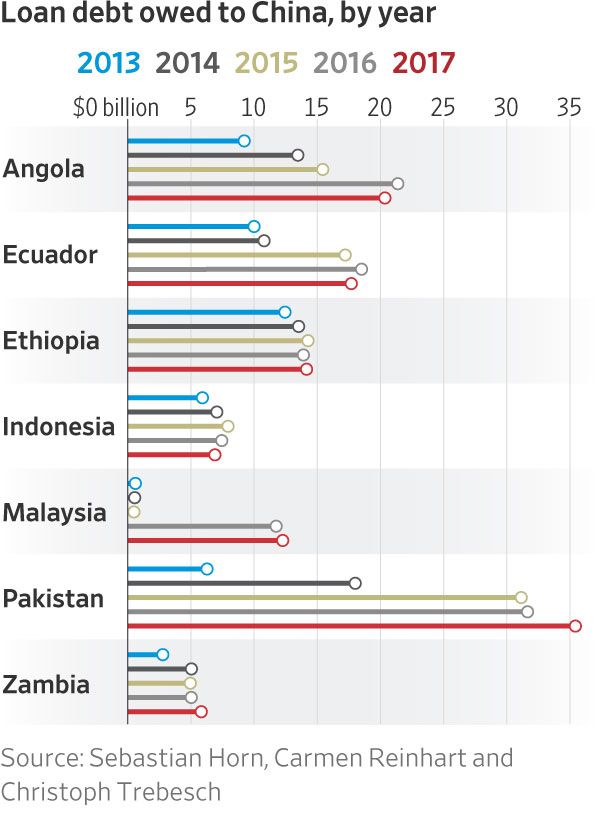

Since the start of the year, dollar-denominated government bond prices have fallen by around 50% or more for some resource-rich countries like Angola and Ecuador that also owe heavy debts to China. An index tracking emerging-market sovereign bond performance has fallen around 16% while more than $80 billion has flowed out of emerging-markets stocks and bonds since the market turmoil began, according to the Institute of International Finance.

China’s rise as a trading and manufacturing power has been extensively studied over the last four decades, but its impact as a financial power is less understood. Exactly how much China has lent is kept under wraps by state-run banks such as China Development Bank and the countries receiving the loans. China’s opaque lending can lead investors and organizations to underestimate the risk they are taking when they make loans to these countries or buy their bonds, leading them to lend at rates that might be too low given the potential losses. These include global investors and multilateral lenders such as the World Bank.

Investors “have to be very, very leery of what’s going on,” said Carmen Reinhart, a Harvard University economist and former IMF official who has studied China’s lending practices.

Ms. Reinhart, one of the most influential U.S. economists on financial crises, was part of a team that over the last two years pieced together a data set of Chinese loans. A resulting study by Ms. Reinhart and economists Sebastian Horn and Christoph Trebesch concluded more than $200 billion of Chinese overseas loans–around half of all its cross-border lending–was hidden from public view. Around a dozen of the poorest countries owed debts to China equal to 20% or more of their annual GDP, the research estimated.

“The problem gets most acute in crisis situations,” said Mr. Trebesch.

Much of the growth can be traced to China’s sprawling “Belt and Road” initiative, which seeks to open up new trade routes, expand overseas opportunities for Chinese firms and deepen the country’s strategic influence through the financing and building of infrastructure.

PHOTO: ASIM HAFEEZ/BLOOMBERG NEWS

Large commodity exporters that seek to sell to China are among the roughly 70 countries taking part in China’s program, many of which took on Chinese debt during the boom in commodities prices, but whose finances are particularly vulnerable to plunging commodity markets today.

Foreign Expansion

China’s ‘Belt and Road’ initiative helps Chinese business abroad.

“The debt burden from these projects is very quickly going to become unsustainable for many, many, many countries,” said Danny Russel, the State Department’s top diplomat for East Asia affairs under President Obama. “This is scary stuff.”

Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy and which depends heavily on oil exports, was one such recipient. Official statistics have presented China as a modest financier for Nigeria in recent years. By the end of 2017, Nigerian government statistics show external debt owed to China was under $2 billion.

In reality, the total debts Nigeria owed to China were more than double that amount, according to the research. Chinese loans have financed infrastructure such as a light-rail project for the capital city of Abuja. Last year, China also committed $629 million in financing for the country’s first deep-sea port. Nigeria’s government is trying to borrow an additional $17 billion from the state-controlled Export-Import Bank of China.

China’s lending, most of which is done in dollars, starkly contrasts that of multinational institutions such as the World Bank. While these groups lend money at below-market rates, China tends to lend at commercial rates, at times securing loans with a country’s oil or other natural resources.

Parallels to the 1980s debt crisis in Latin America—which spurred a “lost decade” of growth for Mexico and others—concern economists today. Just like the earlier case, a prolonged commodities boom fueled lending to resource-rich developing nations. Some economists say China’s opaqueness in its lending is reminiscent of the syndicated U.S. bank loans that crippled Latin America decades ago.

“The thing about the Chinese lending is it’s not transparent,” said Kevin Daly, investment manager for emerging-market debt at Aberdeen Standard Investments Inc. “Countries that do borrow from the Chinese, when you meet with their officials they do offer you a figure, but they don’t offer you details of the breakdown or the repayment schedule.”

Southeast Asia has proven a particular focus for Belt and Road projects. Malaysian debts owed to China are estimated to have surged from less than a billion dollars when the initiative launched to more than $12 billion at the end of 2017. In Indonesia, a $4.5 billion loan agreement with China Development Bank is helping the country to push ahead with its first high-speed rail project.

An economic crisis in Pakistan exemplified the risks. As a showcase of the Belt and Road program, China planned a $62 billion building spree across Pakistan, with China-backed ports, railways and other infrastructure to boost growth.

But Pakistani officials now say they hadn’t properly assessed Pakistan’s fiscal outlook when accepting Chinese loans and projects, which required the use of Chinese contractors in exchange for financing. Chinese-financed power plants, for instance, placed onerous financial obligations on the government, and contributed to a debt crunch that forced Pakistan to seek a bailout from the IMF. Islamabad denies that its debt problem is related to China.

China’s government has also denied engaging in what critics call “debt-trap diplomacy.” State-run lenders China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China didn’t respond for comment.

China’s actions have garnered deeper scrutiny among U.S. officials, with the Trump administration nominating a critic of China’s foreign lending practices to lead the World Bank. David Malpass has used the position as the institution’s president to continue pushing China for more transparency, recently criticizing what he described as nondisclosure agreements written into Chinese foreign lending contracts.

“So, as the IMF or the World Bank goes into a developing country and says, ‘What are your debts?’, the country can’t tell you because they have a nondisclosure clause that’s really tightly written,” Mr. Malpass said in February.

U.S. criticism comes against the backdrop of an intensifying rivalry between the world’s two biggest economies, which the coronavirus crisis has only inflamed. A specific concern, current and former U.S. officials say, is that China uses indebtedness of weaker neighbors to gain leverage over them and pursue strategic aims.

A global recession may lead indebted countries to seek new terms with Chinese lenders, investors say, although it is too early to know how China will respond. Domestic economic constraints in China stemming from the coronavirus may make China less willing to roll over debts as they mature, which could exacerbate emerging-market liquidity challenges.

“China itself is also still recovering from a very huge shock,” said Esther Law, senior investment manager for emerging-markets debt at asset manager Amundi SA. The country “has lots of demands on its resources now.”

— This article was originally published by WSJ.