Halliburton Inc.’s chairman, David Lesar, delivered a rousing message about the smarts of U.S. oil companies on his company’s latest earnings call (and his last):

Now I’ve heard energy investors say that today’s customer behavior shows nothing was learned in the last downturn. That simply is not true. Our customers are smart and adaptive, and they do learn from the past. Their business DNA is to be survivors, and they are. Look at the reaction in the past several weeks. Today, rig-count growth is showing signs of plateauing, and customers are tapping the brakes. This demonstrates that individual companies are making rational decisions in the best interests of their shareholders.

Awesome, right?

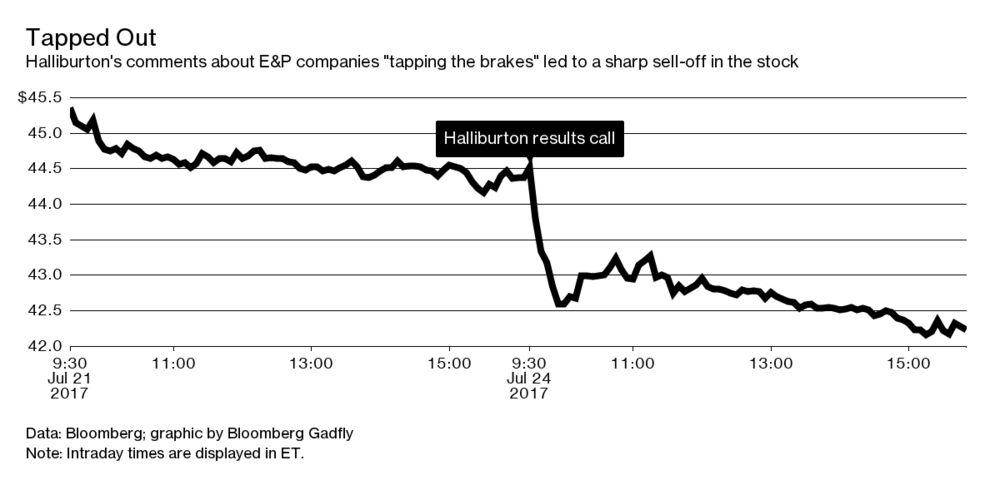

It turns out investors aren’t really jazzed about rationality. Exploration and production is an industry where growth is king and cash merely the power behind the throne. So while Halliburton delivered thumping results on Monday, Lesar’s assessment met with a Bronx cheer.

There are important implications here, not just for Halliburton and its investors, but the wider oil industry.

As for Halliburton, the sell-off looks overdone. While the rebound in U.S. drilling has slowed, Halliburton has a competitive edge in well completions. As I wrote here, a substantial stockpile of drilled but uncompleted wells, or DUCs, has built up, partly because equipment and service suppliers such as Halliburton are sold out. And given the relatively narrow range of oil prices between euphoria and despair in shale — roughly $40 to $60 a barrel — rigs could get taken offline later this year and thereby tee up a rally that pushes them back to work in 2018. As Anadarko Petroleum Corp.’s nuanced tweak to guidance on Tuesday demonstrated — whereby it maintained growth targets for shale oil — tapping the brakes isn’t the same as shutting off the engine.

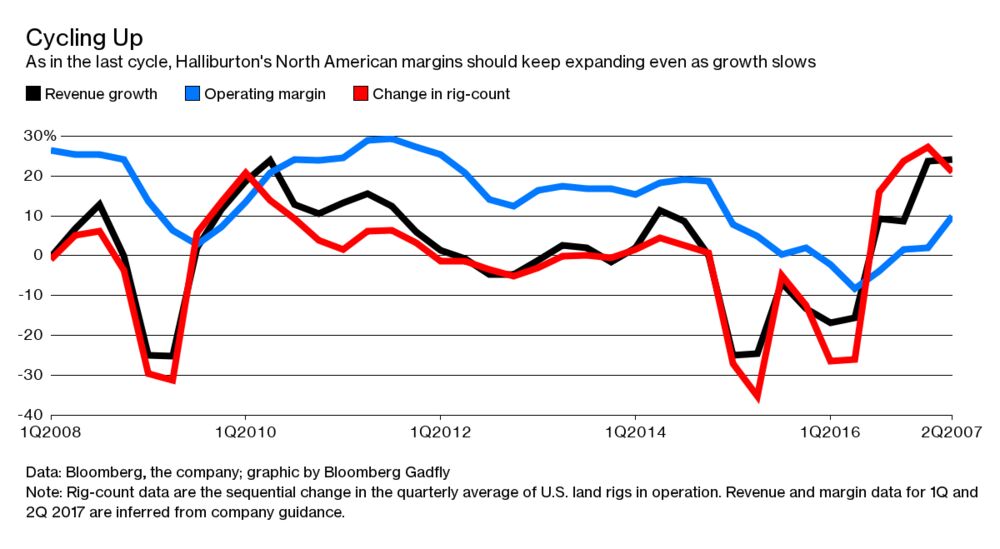

Even as revenue growth in North America moderates alongside the rig-count, Halliburton’s margins should keep rising, partly because it took much of the pain associated with putting people and equipment back to work already:

The broader point concerns those “rational decisions” Lesar mentioned.

His comments could be read as a gossamer-veiled rebuttal to rival Schlumberger Ltd. This was CEO Paal Kibsgaard on Friday:

The production level from the U.S. land E&P companies, which currently represent around 8 percent of global oil supply, is largely driven by the U.S. equity investors, who are encouraging, enabling, and rewarding short-term production growth, in spite of marginal project economics.

Translation: Oil prices are being held down by drill-baby-drill E&P companies, egged on by irrational investors.

On one level, both Lesar and Kibsgaard were talking their respective books. Halliburton’s strength in the U.S. demands optimism about that region, while Schlumberger’s higher weighting overseas means it could benefit in relative terms from American shale cooling.

But their sentiments also intersect with the stance of another interested party making news: the Vienna Group of OPEC members and other countries cutting supply to engineer a price rebound.

Their lack of visible progress in clearing the oil glut, alongside all-too-visible signs of dissension in the ranks, is pushing more of the burden onto the shoulders of de facto leader Saudi Arabia. This weekend’s interim meeting resulted in an announcement expressing “confidence” — but which simultaneously undercut it by leaving open the option of extending the supply agreement (again) beyond next March if it hasn’t worked by then.

The reason Saudi Arabia’s shaky coalition struggles to impose discipline is that, hard as it is to herd a couple of dozen cats in Vienna, expecting unity from thousands of companies in the shale patch is just a fool’s errand. That was the other message from Halliburton’s Lesar on Monday:

Currently, there’s a strongly held view by energy investors that the U.S. independent operators behave as a group. That view is wrong. When thousands of companies make discrete decisions about the same market each day, they do have a tendency to swing the activity and production pendulum too far one way or the other. That is not group-think. It is the impact of individuals trying to do the right thing for their investors.

There was an element of chest-thumping to Lesar’s words, but he nailed the fundamental force that has upended the oil market.

Back in March, OPEC’s secretary general told a conference crowd in Houston he wished the shale boom could have happened “in an orderly fashion.” But it couldn’t happen in any other way than it did. What differentiates shale from what came before is the intensity of its competitive struggle and prioritisation of learning-by-doing rather than just scale to cut unit costs.

E&P companies and their investors, as in any other industry, aren’t always “rational” as they strive to do this.

Then again, neither were those investors who backed the supermajors as they ploughed hundreds of billions of dollars into mega-projects. Nor are the ones now banking on Vienna’s coalition of the barely willing to take charge. The continuing search for balance and order distracts from the essentially chaotic forces that now rule the market.

By Liam Denning/Bloomberg