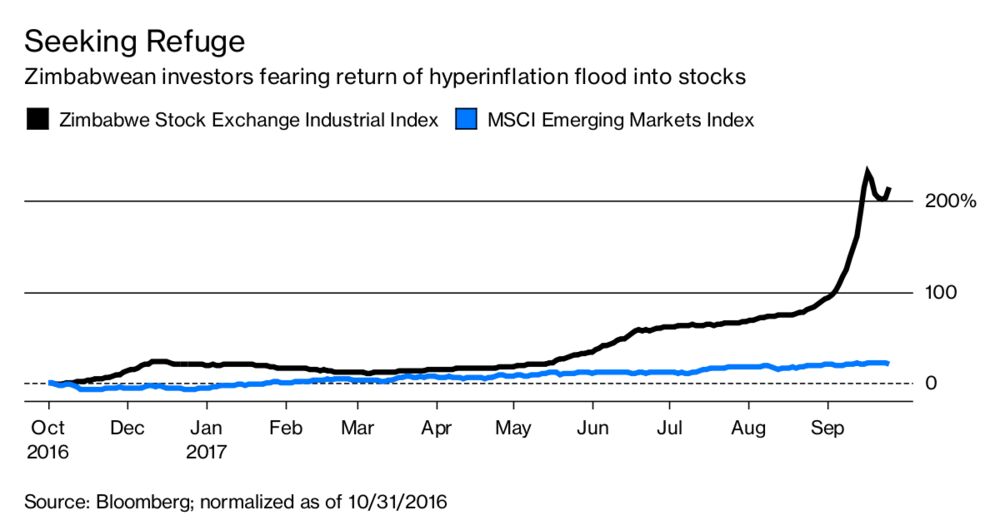

Robert Mugabe’s latest economic experiment is making Zimbabwe’s stocks the world’s best performers for all the wrong reasons.

And there are little foreign investors like Franklin Templeton, JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Allan Gray can do to escape: it’s practically impossible for them to pull out their money.

Economic chaos has been a regular feature of investing under Mugabe’s 37-year reign because he frequently blindsides markets with policies that have devastating consequences. The latest ploy—trying to solve a crippling currency shortage by printing a new form of money—is stirring memories of the 500 billion percent inflation (no, that’s not a typo) of a decade ago.

Zimbabweans are using equities as a refuge as the central bank prints hundreds of millions of its new so-called bond notes. They’re worried inflation will spiral and want to preserve their wealth. Going to the bank to withdraw cash isn’t an option because most lenders are short on U.S. dollars, which has been the main currency in use since Zimbabwe scrapped its own worthless dollar in 2009.

So they’re buying what they can electronically—appliances, cars, gold, property or, for those with limited resources, shares like those of African Distillers Ltd. that go for $1.70 each after more than doubling this month. The benchmark equity index has tripled since the first batch was issued in November, including a 62 percent jump in September as 300 million worth of bond notes were released into the money supply.

Foreign investors like JPMorgan and Templeton, which sold some holdings before the currency crunch got really bad, are stuck watching the crisis unfold. He and other managers of African and frontier funds are invested in Zimbabwe because at $11 billion, its market capitalization is bigger than Botswana, Ghana and Zambia combined. Companies like Delta and Econet are also doing well financially by catering to the country’s 14 million consumers.

As little as two years ago, pulling money out of Zimbabwe wasn’t as hard. The central bank made $231 million available in 2015 to pay investors abroad to repatriate cash, but that sum fell to $5 million in 2016 and just $700,000 in the first quarter of this year.

The more the market rallies, the more Allan Gray fund manager Nick Ndiritu discounts the value of the Zimbabwe stocks in his $351 million portfolio dedicated to Africa, excluding South Africa. Just over a quarter of the fund is invested in Zimbabwe, in companies like Delta and Econet.

“We will continue to focus on the fundamentals, even if the market doesn’t,” said Cape Town-based Ndiritu, who’s slashed the value of the holdings by 40 percent already. “It’s a very unpredictable environment and it’s difficult to say what it’ll be like a year or two down the line.”

It’s not the first time Mugabe has caught investors unaware. Take his sanctioning the violent takeover of white-owned farms starting in 2000, which throttled agriculture, a mainstay of the nation’s economy. Or his central bank’s rush to print Zimbabwean dollars in the following years to pay off mounting debts, which triggered hyperinflation and the last currency crisis. At 93, he’s still eager to run for re-election next year.

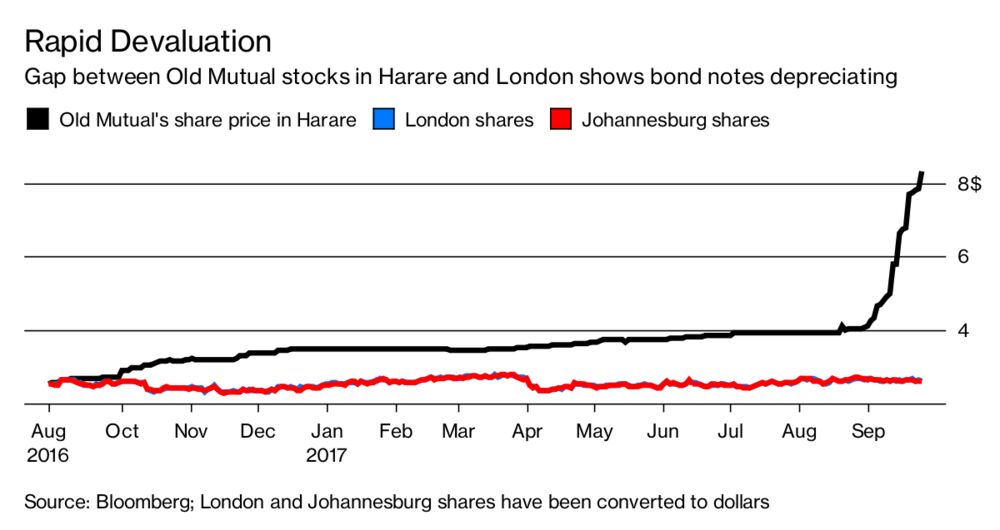

Many citizens worry the bond note may be a precursor to Zimbabwe officially adopting a new currency, forcibly replacing the U.S. dollar in which their savings—and shares—are denominated. While the central bank says bond notes are worth the same as the U.S. dollar, small shops and gas stations in Harare charge 30 to 40 percent more if people use them rather than authentic greenbacks.

“Instead of me having a fictitious bank balance, I would rather invest the money on the stock market,” said Walter Moyo, a 39-year-old shop manager in Harare who recently purchased shares in Delta, Econet and African Distillers.

For a sense of the true value of the pseudo currency, the dollar-denominated shares of Old Mutual in Harare trade at a 200 percent premium to those listed in South Africa and London. Given that no one can actually profit from that difference, it implies that, in investors’ eyes, the bond note is more than 60 percent weaker than the U.S. dollar.

“The market will continue to increase the bond note discount to the U.S. dollar,” said Mobius. “As long as the liquidity situation worsens and the government is not able to address it, the bull-run is likely to continue.”

Report courtesy Bloomberg