Joy Agwunobi

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly shaping global competitiveness, offering transformative potential in sectors such as education, healthcare, agriculture, creative industries, and access to justice. However, for Africa, the promise of AI remains unevenly realised.

These issues have been central to discussions at recent Global AI Summits focused on Africa, where organisations such as Bibliothèques Sans Frontières (Libraries Without Borders), Kajou, and the AI Lab Pleias emphasised the importance of ethical, culturally relevant, and inclusive AI.

In April 2025, these groups launched a white paper titled “Beyond the Hype: Building Equitable and Sustainable AI for Social Impact” under the Ideas AI initiative. The publication stressed that without deliberate intervention, the technology could become a tool primarily benefiting wealthier nations, leaving underserved communities further disadvantaged.

A core concern of the white paper is the severe underrepresentation of African languages in AI datasets. With over 7,000 languages worldwide, approximately 2,000 are spoken across Africa. However, the models overwhelmingly prioritise English and other high-resource European languages. Over 90 per cent of training data focuses on English, while less than 1 per cent accounts for thousands of African, Asian, and indigenous languages. This systemic bias limits AI’s capacity to process local dialects, indigenous knowledge, and cultural reasoning frameworks.

The study warns that AI could accelerate language loss currently, one language disappearing every three months, while excluding indigenous knowledge from digital platforms, depriving future generations of culturally rich insights.

Beyond language, the white paper highlights infrastructural disparities that hinder equitable adoption. Africa, home to 17 percent of the global population, accounts for less than 1 per cent of global data center capacity. Internet penetration in Africa averages just 37 percent, compared with over 90 per cent in North America and Western Europe.

To address these challenges, the white paper proposed six key recommendations: investing in frugal, resource-efficient, and offline AI; promoting linguistic and cultural inclusion through open-source tools; enforcing ethical AI governance with human oversight; prioritising transparency in AI models and datasets; adopting culturally relevant evaluation metrics; and building local AI capacity through education, research, and entrepreneurship.

The ITU–UNESCO State of Broadband in Africa report, published in September 2025, reinforces many of these concerns, while providing additional context on AI applications and progress. According to the report, limited online texts and image datasets in African languages mean outputs are often biased, culturally inaccurate, or unrepresentative. Digital translation, in particular, suffers, as concepts may be imposed from outside African contexts, potentially misleading users.

However, private sector initiatives are gradually filling these gaps. Google, for instance, incorporated several African languages including Yoruba, Hausa, Igbo, Zulu, and Somali—into its Translate service as early as 2013. In 2022, the company launched its 1,000 Languages Initiative, supporting around 25 African languages and their dialects through Zero-Shot Machine Translation. These tools are already enabling applications in local language dubbing, storytelling, agricultural knowledge preservation, and content accessibility.

The ITU–UNESCO report also highlights how AI applications are expanding across promising sectors in Africa. In agriculture, AI tools are being deployed to boost crop yields, optimise irrigation, and detect pests and diseases. Creative industries are exploring it for artistic production, with ongoing efforts to protect intellectual property rights in the digital environment. Business intelligence and trade competitiveness are other areas where AI is gaining traction.

Despite these advances, regulatory frameworks across the continent remain a work in progress. Governments are seeking to balance oversight with flexibility, adapting policies to accommodate emerging technologies while protecting communities. Progress in connectivity and innovation is increasingly being driven by collaborations between governments, civil society, and the private sector, enabling African entrepreneurs to explore digital solutions tailored to local needs.

Building on these collaborative efforts, Nigeria has positioned itself at the forefront with the launch of the Nigerian Atlas for Languages & AI at Scale (N-ATLAS).

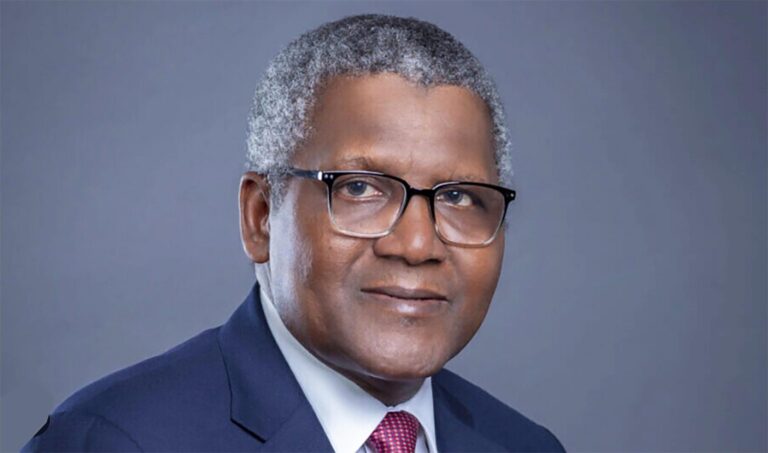

Bosun Tijani, Nigeria’s minister of communications, innovation and digital economy, emphasised that the project demonstrates Africa’s proactive role in shaping the AI landscape.

“Our goal is to advance natural language processing for underrepresented languages, and in doing so, showcase Nigeria’s leadership in building digital public goods that will empower the continent and contribute to global AI development,” he said.