W

Why?

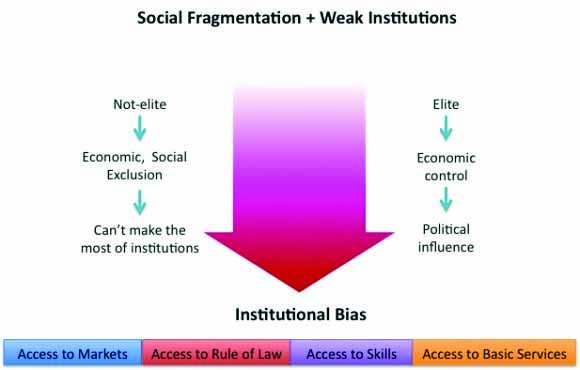

Because inequitable institutions goes to the heart of the matter—to why the politics of fragile states are so unstable, to why developing countries often grow in ways that only enriches a small segment of their populations, and to why reform requires a significantly different approach than typically suggested.

Roughly one-half of the developing world’s population—some three billion people—is disadvantaged because of the inequities embedded within how their governments and economies work. As I write [in the book],

“Lack of opportunity is so widespread and its impact so powerful in less-developed countries because of the nature of their societies. Weak government and divided populations combine to create a governing system that inevitably produces inequitable social relationships and self-interested politics that work against the interests of the weak and deprived. And the two factors reinforce each other in a poisonous mix that has long-term effects on how countries are governed, and how the poor live. As a consequence, hard work alone cannot help those at the bottom of society build more comfortable and secure lives….

…Of course social divisions by themselves do not cause inequities. Every market economy has them. But where societies are weakly integrated, such inequities are likely to be far greater because the mechanisms for spreading wealth—markets and governments—break down….

The combination of inequality and exclusion both creates poverty and perpetuates it. Starting with little income and meager assets, the poor are excluded from the resources, opportunities, information, and social networks necessary to improve their condition. Imbalanced distributions of public spending, unfair laws that privilege one group over another, and officials beholden to powerful interests all play their role. Discrimination in land and water rights, access to schools and financial institutions, and job markets all work to reduce the scope for the poor to use their own initiative to improve their circumstances….

While governments in most countries generally strive to moderate such divisions—by, at the very least, offering equal protection before the law to everyone—in deeply divided societies they often exacerbate them. Beholden to a segment of the population, politicians, bureaucrats, and judges end up directly and deliberately perpetuating social exclusion. (In many cases, groups of people are not actually entirely excluded but are included on terms that make it all but impossible for them to compete economically and politically with other groups….) The vicious cycle—of social exclusion producing unfair governments, which in turn produce social exclusion—feeds off of itself.”

A recent book, The Locust Effect, documents the inequity of institutions in great detail by focusing on how the criminal justice system in developing countries disadvantages those without money or connections. It is both a great read as well as a great tutorial for anyone wanting to understand how the poor actually live in much of the world.

Instead of focusing on housing, water, health, hunger, education, or income—what just about everyone else working on poverty reduction does— Gary Haugen and Victor Boutros focus on the institutions that most impact the lives of the poor. They argue that violence, insecurity, and abuse at the hands of the police and criminal justice system are so widespread—using examples from India to Peru to the Philippines—as to be a “terror,” humiliating, violating, defiling, and degrading, yet “such a part of the air they breathe.” The consequences are devastating: “Common violence—like rape, forced labour, illegal detention, land theft, police abuse, and other brutality—has become routine and relentless,” ruining lives, blocking roads out of poverty, and undercutting development.”

“Corruption of the police force in the developing world means that the poor are priced out of the very protections against violence upon which everything else depends…. Corruption places the poor in a bidding war against perpetrators who are making counter offers to the police to not enforce the law. As sexual assault survivors from the slums of Nairobi explained… They did not report their employers’ repeated sexual assaults…to the police “because our employers would have been able to bribe them.” In practical effect, corruption allows violent predators to purchase hunting licenses from the authorities to hunt down the poor…

Once corruption becomes endemic in the police forces, the entire concept of “law enforcement” becomes inverted to serve the money-making enterprise. Every law and regulation ceases to be seen as an authorization to restrain a socially hurtful behaviour and is seen instead as an opportunity to extract money from the public. Police even come to use the cloak of “law enforcement” to initiate and run their own criminal enterprises such as sex trafficking, drugs smuggling, illegal mining, or logging enterprises. Police provide muscle and intimidation for criminal enterprises, and gathering intelligence for gangs; and they act as hitmen, assassinating and threatening those whom they are charged with protecting.”

I recommend The Locust Effect to anyone who wants to understand how institutions in developing countries actually work—and why change is about a lot more than just improving policy, technical training, and so on. Gary Haugen’s NGO, International Justice Mission, is one of the few organizations that does institutional reform well. Most donors spend large sums of money on this problem but rarely make large impacts, as many studies of governance reform spending can testify. Only by directly engaging institutions from the inside-out is change really possible—and few development agencies have the patience, insider knowledge, appetite for risk, and flexibility to handle the process.

The field needs more people like Gary Haugen and Paul Farmer who are tackling this challenge. It also needs to focus much more on building up the governance ecosystem—everything from law schools to governance academies to universities to think tanks and media—that indirectly have large impacts on how states work. Change from the inside, ground-up, will always be more practicable and likely to reach scale.